|

# 522:

©

Hilmar Alquiros,

Philippines

Hilmar Alquiros

Nothingness and Being

Potentialities of Ontological

Evolution

All rights

reserved by

© Dr.

Hilmar Alquiros, The Philippines, 2023

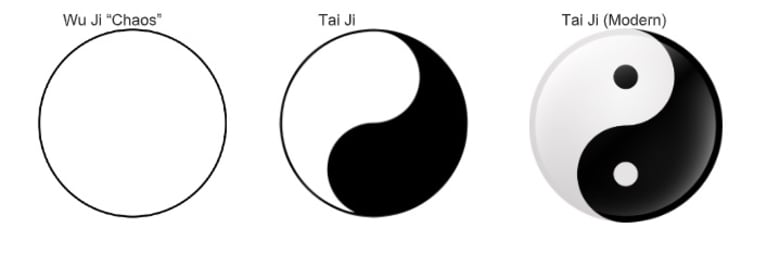

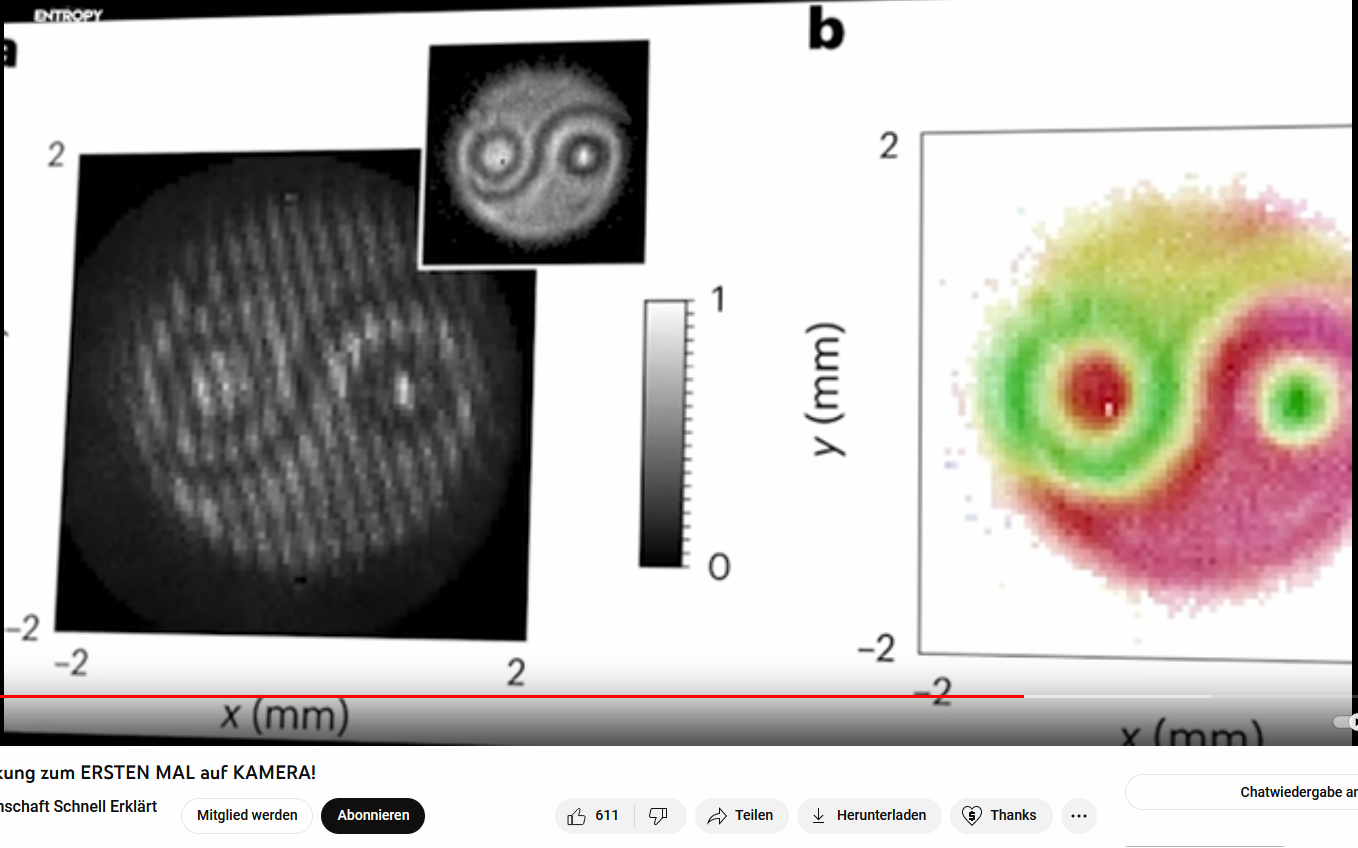

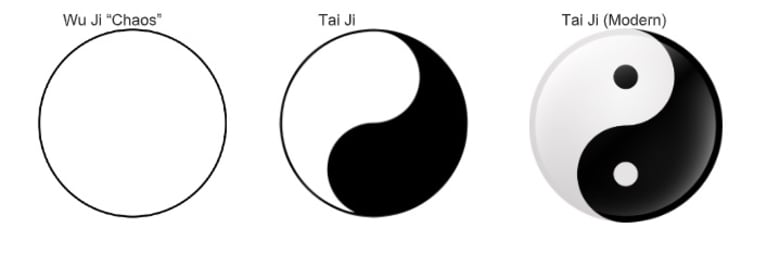

Yin 阴 + Yang 阳

陰 yīn, 'the

shadowy side of the hill', 陽 yáng, 'the

sunny side of the hill'

→

Feedback |

|

0

-

Introduction

A - Why is there

Something rather than Nothing? Why

is there Anything at all and not Absolute Nothing?

B - Absolute Nothingness and Potentialities, between

Nothing and Something

C - Dao 道

as Absolute Nothingness AND Everything

D -

Appendix:

Nothing and Humor!

E -

Epilogue

0 -

Introduction

0.0.

PROLOGUE: A World...

with or

without a Beginning?

0.1.

The Question of

Being: Leibniz and Heidegger

0.2.

Levels of Nothing =

Types of Potentialities

-

Everything and every thing

as a part of the Universal Evolution

-

Ontological Evolution:

Potentialities

-

Levels of

Beingness

-

Levels of

Nothingness

0.3. Basic

Terms of the Philosophy of Reality

-

Ontological

Pluralism

-

Concreteness

and Abstractness

-

Contingency

and Necessity

-

Possible

Worlds + Probabilistic Explanation

-

The

Possibility of Nothing

-

Gradation of

Being

-

Metaphysical

Nihilism + Subtraction Arguments

-

Ontology of

the Many

-

The

Principle of Sufficient Reason

-

The Grand

Inexplicable

-

Ultimate

Naturalistic Causal Explanations

-

Complete

Explanation of Everything

-

Conceiving

Absolute Greatness

0.4.

Selected

Sources about the Topics

-

Selected General

Sources

-

Wikipedia Sites

-

Further

Reading

|

|

A - Why is there

Something rather than Nothing?

Why

is there Anything at all and not Absolute Nothing?

A.1.

The Conceptual Field of Nothingness

-

Basic Terms

-

Related

Linguistic Concepts and Nuances

-

A Systematic

Overview of the Concepts

A.2. Formulations

and

Basic aspects

of the Question of

Being

-

Formulations of the Existential Question

-

Exploring the Existential Question

-

Cosmological Perspectives on the Origin of

Existence

-

Philosophical Approaches to the Question

-

Linguistic Criticisms to the Question of Being

A.3. Why Questions

-

Why Are

There Any Beings at All?

-

Why Are

There Any Concrete Beings?

-

Why Are

There Any Contingent Beings?

-

Why Are

There the Concrete / Contingent Beings?

-

Why Do

Concrete / Contingent Beings Exist Now?

-

Why Is There

Not a Void?

A.4.

The Role of Consciousness

in Reality

-

Emerging Theories and Future Directions

-

The Interplay between Science, Philosophy, and

Spirituality

A.5.

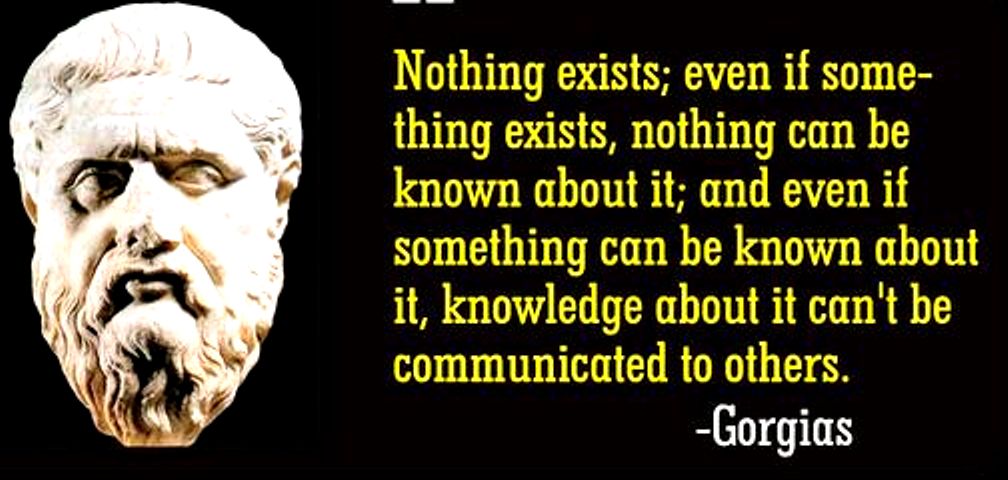

Ancient Greek

Philosophy: The Birth of Metaphysics

-

A Perennial Inquiry

-

Plato

-

Parmenides

-

Aristotle

-

Plotinus

A.6.

Medieval Philosophy:

Theological Perspectives on Existence - 'creatio ex nihilo'

-

Christianity and Islam

-

Thomas Aquinas and Avicenna

-

Fridugisus' answer to Charlemagne(!)

-

Meister Eckhart

A.7.

The Enlightenment:

Rationalism and Empiricism

-

Enlightenment

-

Kant

-

Hume

-

Carnap

A.8.

Philosophical

Approaches to the Question

-

-

-

-

A.9.

Cosmological

Perspectives on the Origin of Existence

-

-

A.10.

The Role of

Consciousness in the Universe

-

-

Panpsychism: Consciousness as a Fundamental

Aspect of the Universe

A.11.

Emerging Theories

and Future Directions

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

A.12.

The Interplay

between Science, Philosophy, and Spirituality

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

A.13. Ultimate Questions and Answers!

-

-

The

Great Alternative:

Something emerging from Nothing versus existing Infinitely

-

Typology of Physical and

Non-Physical First Causes

-

-

|

|

B - Absolute Nothingness and Potentialities, between

Nothing and Something

B.1. Origins of Absolute

Nothingness

-

-

-

-

B.2. Idealistic

Potentialities - A Closer Look

-

-

-

-

-

Idealistic

Potentialities - created or uncreated?

B.3. From Nothingness to

Something: A Logical Transition Through Emergentism and Process

Philosophy

-

-

B.4. The Role of

Absolute Nothingness in Existential Philosophy: Exploring the Human

Condition

-

-

-

B.5. Embracing the

Potentialities: Practical Applications

-

-

-

-

-

B.6. The Intersection of

Science and Philosophy: Quantum Mechanics, Absolute Nothingness, and

Consciousness

-

-

-

B.7. Expanding

Consciousness and Embracing the Unknown

-

-

-

B.8. Ethical

Implications of Idealistic Potentialities

-

-

-

B.9. A Catalyst for

Spiritual Exploration and Growth

-

-

B.10. The Aesthetic

Dimension: Art, Music, and Literature Inspired by Absolute Nothingness

and Idealistic Potentialities

-

-

B.11.

The Impact of Technology and the Digital Age on Absolute Nothingness

and Idealistic Potentialities

-

-

-

B.12. The Future of

Absolute Nothingness and Idealistic Potentialities: Continuing the

Exploration

-

Continuing the Exploration Through

Interdisciplinary Collaboration while Embracing the Paradoxical Nature

of Reality

-

B.13. Cross-Cultural

Perspectives on Absolute Nothingness and Idealistic Potentialities

-

Philosophical and Religious Traditions

-

-

-

-

B.14. The Role of

Language in Conveying Absolute Nothingness and Idealistic Potentialities

-

-

-

-

B.15. The Interplay of

Science, Art, and Philosophy in Understanding Absolute Nothingness and

Idealistic Potentialities

-

-

-

-

-

B.16. The Opposite Direction: From

Something to Absolute Nothingness

-

-

-

-

|

|

C - Dao 道

as Absolute Nothingness AND Everything

C.1. Dào

道 and Nothingness 無極 wújí

-

Basic Concepts

-

Laozi - Daodejing

-

Daoist and Western Concepts of Nothing

C.2. Exploring the

Foundations of Daoism

-

-

C.3. The Concept of Dao:

Embracing Nothingness and Everything

-

-

C.4. Daoist Principles

for Harmonious Living

-

-

C.5. The Daoist Path to

Enlightenment

-

-

C.6. Delving Deeper into

Dao as Unfathomable Nothingness

-

-

-

-

-

C.7. Dao as Absolute

Nothingness: Embracing the Immeasurable

-

-

-

-

-

The Profound Implications of Dao as Absolute:

Nothingness and Everything

C.8. The Harmony of

Opposites: Navigating the Dynamic Interplay in Daoist Philosophy

-

-

-

-

-

C.9. The Timeless

Relevance of Daoist Philosophy: Unveiling the Universal Truths of

Beingness

-

-

-

-

-

-

C.10. The Ineffable and

the Manifest Dao: Its Sublime and Poetic Potentialities

-

The Profound Elegance of the Dao

-

-

-

-

-

C.11. The Concept of

Creation in Daoist Philosophy

-

Comparison with the

Judeo-Christian concept

-

Comparison with the Neoplatonic

concept

-

The Daoist

Concept of Creation

-

Similarities and Differences

-

Tabular Comparison of Key Features

|

|

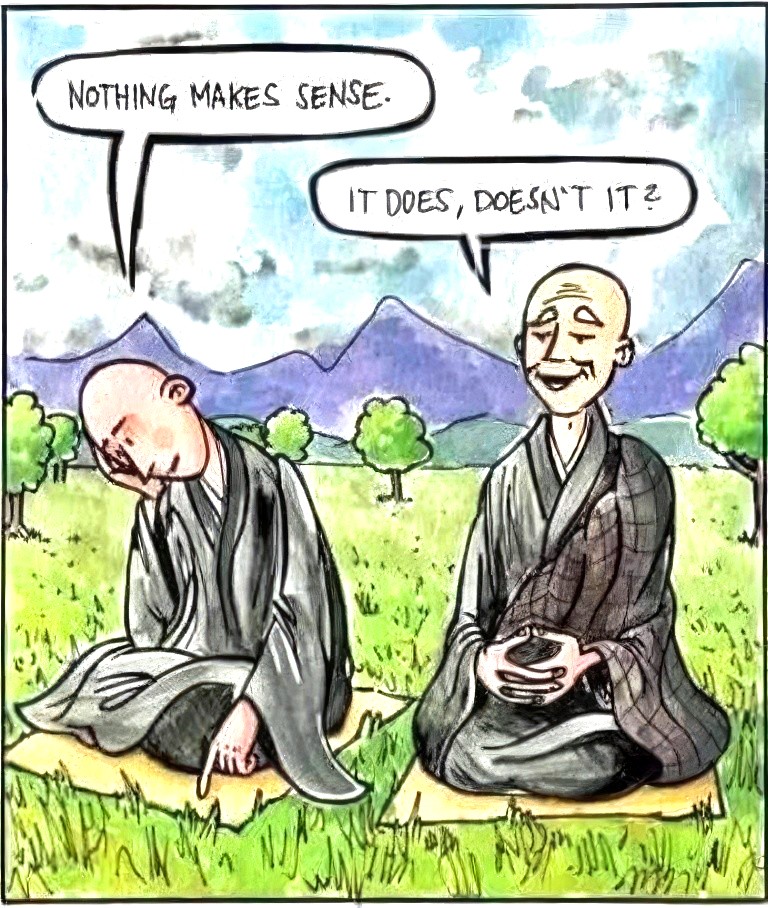

D - APPENDIX:

Nothing and Humor!

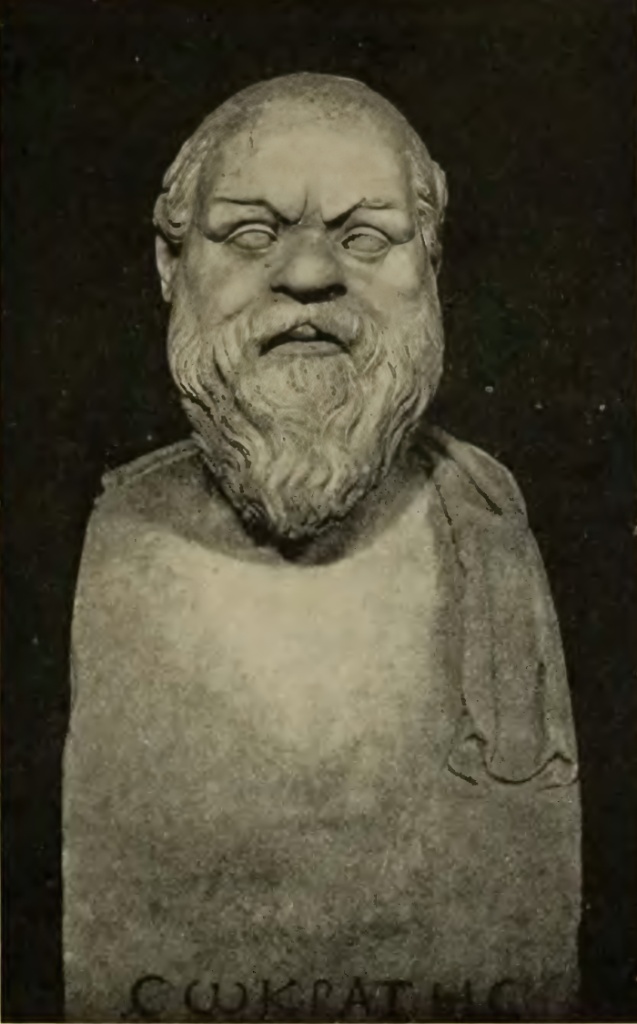

D.1.

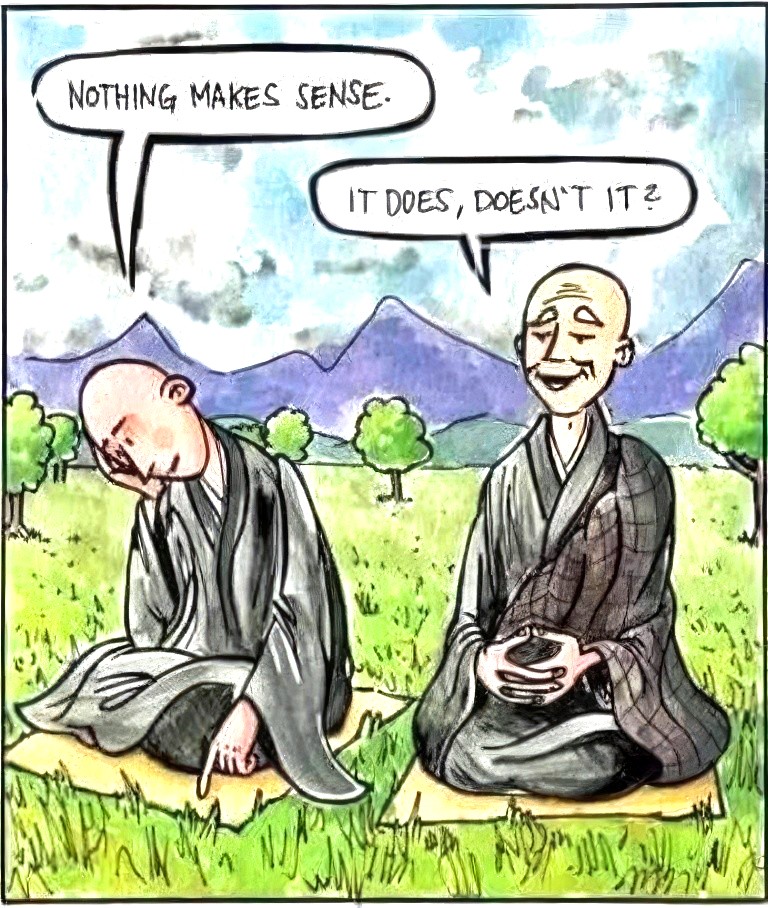

Socrates meets Laozi!

D.2.

Out of

Nothing?

D.3.

Skills

and Ingredients a Creator needs...

D.4.

The

Cosmic Wednesday

D.5.

Zeit-Bombe

/ Time-Bomb

D.6.

Three

A.I.s on the Question of Existence

D.7.

Has LaMDA

Become Sentient?

D.8. Nothingness

|

|

E - EPILOGUE:

E.1.

Heidegger's Concepts of Nothingness

E.2. Different Perspectives and Arguments for or

against Creator/Creation Concepts

E.3.

The

Ultimate Question of Ontological Evolution |

0

|

„And

in every beginning there is something magical that protects us and helps us to

live.“

Hermann Hesse,

„Stufen“

(Stairs)

0.0. Prologue: A World with or without a Beginning?

The topic of whether the

universe has existed eternally or had a definite beginning is a

significant one in philosophy, physics, and theology. The concept of a world that

has existed since eternity, often referred to as an Eternal Universe or a

Steady-state Universe, and the idea of a world that had a beginning and was

created out of nothing, often associated with the Big Bang theory, are

two contrasting perspectives on the origin and nature of the universe. While

scientific understanding and evidence predominantly support the

latter, let's explore some arguments and viewpoints related to both

perspectives.

|

A World... |

...with

a Beginning |

...without

a Beginning |

|

Scientific Theory |

The Big Bang Theory:

The

universe began with the Big Bang about 13.8 billion years ago. This

theory is supported by a wide range of empirical evidence, including

the redshift of distant galaxies, the abundance of light elements

like hydrogen and helium, and the cosmic microwave background

radiation. |

Eternal Inflation:

Some models of cosmic inflation propose that

the universe as a whole is eternally inflating and that what we see

as the „universe“ is just one bubble in a Multiverse. This allows

for a universe that, on the largest scales, has no beginning or end. |

|

Physical Law/Principle |

Second Law of Thermodynamics:

This

law states that the entropy of an isolated system always increases

over time. If the universe had existed forever, it would now be in a

state of maximum entropy, which we don't observe. Therefore, it's

suggested that the universe must have had a lower-entropy beginning. |

Quantum Gravity:

In theories that unite quantum mechanics with

gravity, like loop quantum gravity or string theory, the Big Bang

singularity is often replaced with a different structure, like a

bounce, implying that our universe is just the latest cycle in an

eternal series. |

|

Philosophical Argument |

Avoidance of actual infinity:

The idea of an actual infinite number of past

events is seen by some philosophers as leading to logical paradoxes.

Therefore, they argue, time must have had a beginning. |

Avoidance of causal regress:

If

the universe had a beginning, one might ask what caused that

beginning. Some argue this leads to a regress of causes that's more

logically coherent to avoid by positing an eternal universe. |

These theories and

arguments are subject to ongoing scientific and philosophical debates. The exact

nature of the universe's origin (or lack thereof) is one of the greatest

mysteries of modern science and philosophy. The scientific consensus

heavily favors the idea of a universe that began with the Big Bang and has a

finite age. The evidence supporting the Big Bang theory, such as redshift

observations, the abundance of light elements, and the cosmic microwave

background, strongly suggest that the universe had a starting point. However,

the ultimate nature of the universe's origin remains a subject of scientific

inquiry and philosophical contemplation, and ongoing research continues to

refine our understanding. The situation is further

complicated by the limitations of our ability to observe the universe and

the complexities of the models used in cosmology.

A World

with

a Beginning = Created Universe

The

Big Bang Theory: This widely

accepted cosmological model states that the universe expanded from a very

high-density and high-temperature state, a singularity, around 13.8 billion

years ago. It is supported by multiple lines of evidence:

-

Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB): The CMB is radiation that's

spread throughout the universe and thought to be a remnant from the early

stages of the universe when it was hot and dense. The existence of the

CMB was a prediction made by the Big Bang Theory, and it was subsequently

observed in the mid-20th century.

-

Redshift of Galaxies: As we observe distant galaxies, we find that

their light is redshifted, meaning the wavelengths of light are stretched

out, indicating that those galaxies are moving away from us. This implies

that the universe is expanding, consistent with the Big Bang Theory.

-

Abundance of Light Elements: The Big Bang Theory predicts specific

amounts of hydrogen, helium, and other light elements. Observations

match these predictions well.

Second

Law of Thermodynamics

This law

states that in an isolated system, the overall amount of disorder, or entropy,

will either remain constant or increase over time. The universe's current state

is not one of maximum entropy, indicating it has not existed forever and must

have had a starting point, or lower-entropy state. If the universe had existed

forever, entropy would be at its maximum, which is not what we observe.

Avoidance

of Actual Infinity

This

philosophical argument states that an actual infinite cannot exist, thus time

must have had a beginning. The idea of an infinite past implies an infinite

sequence of events leading up to the present, which some philosophers and

mathematicians consider to be a paradox or an absurdity. For instance,

traversing an infinite past to reach the present moment appears to be an

insurmountable task.

The

Kalam Cosmological Argument

This

philosophical and theological argument posits that everything that begins to

exist has a cause; the universe began to exist, therefore it has a cause.

This has been used in theology to argue for the existence of an

uncaused cause or a prime mover, often identified as Deity..

Cosmic

inflation and the Big Bounce

While

these models still suggest a beginning to our universe, they propose that

this could be one of many cycles of expansion and contraction,

potentially extending infinitely into the past and future. Here, the notion of

beginning is relative to our universe's cycle rather than absolute.

The

Borde-Guth-Vilenkin theorem

This

theorem suggests that any universe, which has, on average, been expanding

throughout its history, cannot be infinite in the past but must have a

past spacetime boundary. (Arvind Borde,

Alan Guth, and Alexander Vilenki).

A World

without

a Beginning = Eternal Universe

Steady

State Theory

This

cosmological model posits that the universe is infinitely old and maintains a

constant average density. New matter is continuously created to maintain this

density as the universe expands. Though less favored today due to the

observational evidence for the Big Bang theory, it was a significant concept in

the 20th century.

Eternal

Inflation

This model suggests that

the inflationary period of the early universe, a rapid exponential expansion,

continues forever in some regions of the universe. While our observable universe

might have begun with a localized 'Big Bang' event, it is a small part of a much

larger, eternally inflating multiverse. Here, new universes or „bubble

universes“ are continually being created.

Quantum

Physics

Some

interpretations of quantum mechanics suggest that the universe could be uncaused

or self-originated. Here, the notion of time is treated differently, and it's

possible to have an eternally existing universe.

Quantum

Gravity Models

These theories aim

to reconcile the theories of quantum mechanics (which explains the behavior of

particles at the smallest scales) and general relativity (which explains gravity

and the large-scale structure of the universe). In some of these models, like

loop quantum gravity or string theory, the singularity at the Big Bang is

resolved, and it's suggested our universe might be part of a cyclical process of

expansion and contraction, or a multiverse, meaning it didn't have a singular

beginning.

Avoidance

of Causal Regress

This

philosophical argument states that if everything has a cause, then an infinite

regress of causes would occur if the universe had a beginning. To avoid this

infinite regress, it posits that the universe must be eternal. This is often

tied to discussions about the First Cause or Unmoved Mover from philosophy and

theology.

Cyclic

Universe or Oscillating Universe theories

These

propose that the universe has always existed and will continue to do so by

undergoing endless cycles of expansion (Big Bang), then contraction (Big

Crunch), and then re-expansion. The models differ in the mechanisms and

details, but they all propose an eternal universe.

Multiverse

Theory

Some

interpretations suggest our universe is just one of countless universes that

form, expand, contract, or continue to exist parallelly, making the overall

cosmos eternal.

0.1. The Question of Being: Leibniz and Heidegger

First accurate question

and treatment by two Germans geniuses:

- Leibniz: Polymath, Philosopher, Lawyer, Historian, Mathematician (Calculus!,

Binary System!)... called the last universal genius.

- Heidegger,

called the profoundest thinker of the 20th century.

Leibniz 1646-1716

Leibniz 1646-1716

|

„Pourquoi il y a plutôt quelque chose que

rien?“

Principes de la Nature et de la Grace fondés en Raison, 1714

(First in French)

„Warum ist Etwas und nicht etwa Nichts?“

Die Vernunftprinzipien

der Natur und der Gnade,

1714

(Leibniz = German)

„Why is there something rather

than nothing?“

The rational principles of nature and grace, 1714

(translated into English)

Great Axiom -

mostly the second

subquestion was less considered or not even mentioned:

„Nothing

exists without a reason being given (at least by an omniscient being)

a) why it is rather than is

not, and

b) why it is so rather than

otherwise.“

(»pourqoi elles [les

choses] doivent exister ainsi, et non autrement« p.14 §7)

This is a

consequence of the great principle that

„Nothing happens without a reason“,

just as there must be a reason for this to exist rather than that.

|

|

„Warum

ist vielmehr etwas, als nichts vorhanden?“

=

„Why

is there something instead of nothing?“

„Wenn

man diesen Grundsatz [des Zureichenden Grundes] voraussetzt, so wird die erste

Frage, die man mit Recht aufwerfen kann, diese seyn: Warum ist vielmehr etwas,

als nichts vorhanden? Denn das Nichts ist viel einfacher und leichter als etwas.

Noch mehr, gesetzt das gewisse Dinge haben existiren

sollen: So muss man angeben können, warum sie so und nicht anders haben existiren

sollen.“

„If

one presupposes this principle [of the sufficient reason], then the first

question, which one can raise rightly, will be this: Why is there something

instead of nothing? Because nothing is much simpler and easier than something.

Even more, if certain things should have existed: Then one must be able to state

why they should have existed in this way and not in another.“

Gottsched, Johann Gottfried,

(On

Leibniz') Theodicee =

Theodicy,

1744, 774-775:

|

Heidegger 1889-1976

Heidegger 1889-1976

Die

Seinsfrage:

„So

gilt es denn, die Frage nach dem Sinn von Sein erneut zu stellen:

Warum ist überhaupt Seiendes und nicht vielmehr nichts?“

Sein und Zeit,

Was ist Metaphysik 1929,

1935

=

The

Question of Being:

„Thus, it is necessary to ask

again the question about the meaning of being:

Why is being at all and

not rather nothing?“

Being and Time, 1927,

What

is Metaphysics, 1929,

1935

|

„Warum

ist überhaupt Seiendes und nicht vielmehr nichts? … So wurzelhaft

diese Frage scheinen mag, sie hängt doch nur im Vordergrund des

gegenständlich vorgestellten Seienden. Sie weiß nicht, was sie

fragt; denn damit jenes wese, was sie als Gegenmöglichkeit zur

Wirklichkeit des Seienden, zum Seienden als dem Wirklichen, noch

kennt, nämlich das Nichts, muß ja das Seyn wesen, das einzig stark

genug ist, das Nichts nötig zu haben.“

„Why is being at

all, and not rather nothing? ... As deeply rooted as this question

may seem, it only hangs in the foreground of objectively imagined

being. It does not know what it is asking; for in order for that to

exist which it still knows as the counter-possibility to the reality

of the existing, to the existing as the actual, namely the nothing,

there must be the being which is the only thing strong enough to

have the nothing necessary.“

Martin

Heidegger,

Besinnung / Reflection, p. 267.

|

With the appearance of

cosmological ideas such as the Big Bang theory and the Anthropic

Principle, metaphysics itself and the fundamental question were

revived after the so-called death of positivism.

In ihrem Denktagebuch

notiert Hannah Arendt 1955 die Frage: „Warum

ist überhaupt Jemand und nicht vielmehr Niemand? Das ist die Frage der Politik“

und dies – so kann man sagen – ist ihre politische Übersetzung der Grundfrage

der Metaphysik.“ Denktagebuch,

1955, vol 1, p.520

0.2. Levels of Nothing = Types of Potentialities

Everything we call real is made of things that cannot be

regarded as real.

If quantum mechanics hasn't profoundly shocked you, you haven't understood it

yet.

-

Niels Bohr

The atoms or elementary particles themselves are not real;

they form a world of potentialities or possibilities

rather than one of things or facts. -

Werner Heisenberg

-

Everything and every thing

as a part of the Universal Evolution:

-

Ontological Evolution:

Potentialities

-

Levels of

Beingness

-

Levels of

Nothingness

0.2.1. Everything and every thing as a part of the Universal Evolution:

|

Technological

Evolution: Inventions, Artificial Intelligence, Quantum

applications

based on

→

Psychological Evolution: Human

Language, Intelligence, Culture

based on

→

Biological Evolution:

Pre-life

forms, RNA / DNA, Unicellular / Multi-cellular organisms

based on

→

Chemical Evolution: Elements /

Molecules, Anorganic / Organic Chemistry

based on

→

Physical Evolution: Big Bang, Space-Time,

Quantum Fluctuations, Energy / Fields, Separation of Forces,

Inflation / Expansion, Matter / Galaxies

based on

→

Ontological Evolution: Absolute

Nothingness → Potentialities → Something / Any Thing,

Everything = (Fields, Energy, Matter...)

based on

→

Dao, Unfathomable, One, Primal/Ultimate

ground, Creator(s)... |

0.2.2. Ontological Evolution: Potentialities

The ontological evolution

includes different conceivable intermediate stages: after the absolute

nothingness, objective and/or subjective potentialities - before it realizes

itself as duality (positive energy and negative gravitational energy), towards

the laws of nature, constants, dimensions... and towards life, consciousness,

creativity and love. We are referring to a concept that is intrinsically

philosophical, but also has its roots in disciplines such as physics,

metaphysics, cognitive science, and psychology. The phrase inherently implies a

transformation of states: from the state of non-existence („nothing“) to a state

of existence („something“).

The concept of „creating something from nothing“ can be discussed at three basic

levels of existence:

Objective towards Being:

This level refers to the transition from absolute nothingness to potential

existence, encompassing concepts like creation ex nihilo (creation from nothing)

in the realms of metaphysics and cosmology. It involves abstract potentialities,

preconditions, and natural laws, leading to events like the Big Bang or the

creation of a multiverse.

Objective inside Being: At

this level, creation occurs within the physical world and is observable,

although it can involve subjective elements concerning the observer's role in

quantum physics. Examples include the spontaneous creation of virtual particles

in a vacuum, or changes in energy fields as per the laws of physics.

Subjective inside Being:

This level is purely subjective and pertains to phenomena within one's

consciousness, such as the emergence of thoughts, ideas, decisions, and

intuitions. Despite seeming to originate out of nothing, they are products of

intricate cognitive processes.

Absolute Nothingness

→

Potentialities

→ Something / Any Thing, Everything (Fields, Energy, Matter...)

There are three basic levels of

„creating“ something from nothing refer to the different ways

in which something can be said to come into existence.

|

(0)

Objective towards Being: Absolute Nothingness (transcendent, unfathomable) → Potentialities: forms,

ideas, preconditions / natural laws, constants, Big Bang, Multiple Bang,

Creation ex nihilo...-

This zero(!) level

is assumed as objective (or partly subjectiv in idealism) and refers

to the creation of something from Absolute Nothingness. |

It is not

tied to any particular being or consciousness, which is a transcendent and

unfathomable state that exists beyond the physical universe. From this state

arise potentials in the form of natural laws, constants, and conditions that

make the creation of the physical universe possible.

This level involves

potentialities and (pre-)conditions that allow

the creation of physical objects and it also deals with theories about the

creation of the universe itself, such as the Big Bang theory or the

concept of Multiple Bangs (in parallel or successive

„bouncing“ form), which suggest that the universe emerged from a singularity or

series of singularities into the existence of space and time dimensions, fields,

and energy.

Finally, this level includes the idea of Creation ex Nihilo,

which is the idea that something can come into existence from absolute nothing,

perhaps without any intermediate steps at all - by some unimaginable

supernatural entity. Tertullian distinguishes two ways of speaking:

a nihilo, from nothing, without a cause of its own, vs. ex

nihilo: nothing as substance.

|

(1) Objective inside Being: energy in vacuum, virtual particles, fields,

laws of physics...

This

level

is objective (or mixed with subjective concerning the role of an

observer in quantum physics): it involves the new spontaneous creation

of something within the physical world. |

This can include the creation of

virtual particles in a vacuum,

which are particles that arise from the fluctuations of energy in empty

space, as well as the phenomenon of entanglement, where two particles

are connected in such a way that the state of one particle is determined by the

state of the other, regardless of the distance between them.

Also included are

Emergence or emergent effects, where new levels

of complexity in an evolutionary process give rise to completely new

properties, with a new whole that is more than the sum of its parts: In

philosophy, systems theory, science, and art, emergence occurs when an entity is observed to have properties that its parts do not have

on their own, properties or behaviors that emerge only when the parts interact

in a larger whole.

Physicists

often call diverse kinds of Something (energy in vacuum, virtual

particles, fields, laws of physics) as „Nothing“, physics starts empirical after

the Big Bang, inside the universe (and its event horizon). Mind-blowing enough

is the evolution of 10^83 sub-particles from the Big Bang with Planck space

1.616255(18)×10^-35 m and Planck time 5.391247(60)×10^-44 s - but Planck

temperature 1.416784(16)×10^32 K (!!) - from what?!

|

(2) Subjective inside Being:

Phenomena of consciousness / mind / brain,

at least seemingly out of nothing.

This level

is subjective and refers to the creation of something within one's own consciousness: This can include

thoughts, ideas, decisions, and intuitions, which are all subjective

experiences that are created within one's own mind. |

When applied to mental phenomena, this

concept takes on a nuanced and fascinating character. It's about the genesis of

thoughts, ideas, decisions, and intuitions, which appear to spring forth from

the void of the mind, thus giving the

impression of „creating something from nothing“. Let's delve into this

subjective process in a bit more detail:

Thoughts

Thoughts are continuous mental narratives

that form our everyday cognition. They seemingly pop into existence, creating

something from the nothingness of an idle mind. This is often most noticeable

during states of focused concentration or mindful meditation, where the

sudden emergence of a thought can seem like a creation from nothing.

However, it's important to note that these thoughts are generally products of

subconscious processes influenced by our experiences, knowledge, and

emotions.

Ideas

Ideas could be considered as more refined

and purposeful thoughts. They often arise from a synthesis of various thoughts

and previous ideas, often in response to a problem or task at hand. Again, this

might seem like creation from nothing, especially when an idea strikes

unexpectedly or in response to a novel situation. But it's usually the

result of complex cognitive processes operating below the threshold of

conscious awareness.

Decisions

Decisions often feel like they are

born out of nothing, especially when we suddenly feel a clear sense of

resolution after wrestling with uncertainty. In reality, decision-making is a

complex cognitive process involving weighing options, considering potential

consequences, and aligning with our goals and values. Again, while the

decision itself may appear to materialize from nothing, it is the product

of significant cognitive activity.

Intuitions

Intuitions, or gut feelings, often

seem to come out of nowhere. These are quick, automatic judgments that

occur without conscious deliberation. They arise from our brain's ability to

recognize patterns and make associations based on past experiences, even if

we can't consciously articulate what those patterns are. So while an intuition

might feel like it's created from nothing, it's actually rooted in our

prior experiences and learned knowledge.

0.2.3. Levels of Beingness

These categories of Being(ness)

and Nothing(ness) represent a broad spectrum of perspectives on existence. Some

are based on empirical observations and scientific theories, while others are

more philosophical or spiritual in nature. The exact nature and boundaries of

these categories, and how they relate to each other, are matters of ongoing

debate and exploration in many different fields, including physics, philosophy,

theology, and cognitive science.

Back to Big Bang...:

Material

Being

This refers to everything that exists physically and can be

interacted with or observed directly in some way. This includes everything from

subatomic particles like quarks and photons, to atoms and molecules, to larger

structures like cells, organisms, planets, stars, and galaxies. These objects

are subject to the laws of physics and can be studied using scientific methods.

Virtual

Particles

In quantum field theory, virtual particles are temporary

fluctuations in energy that occur due to the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle.

They can't be directly observed, but their effects can be measured, and they are

integral to our understanding of quantum phenomena. They are responsible for

phenomena like the Casimir effect and Hawking radiation.

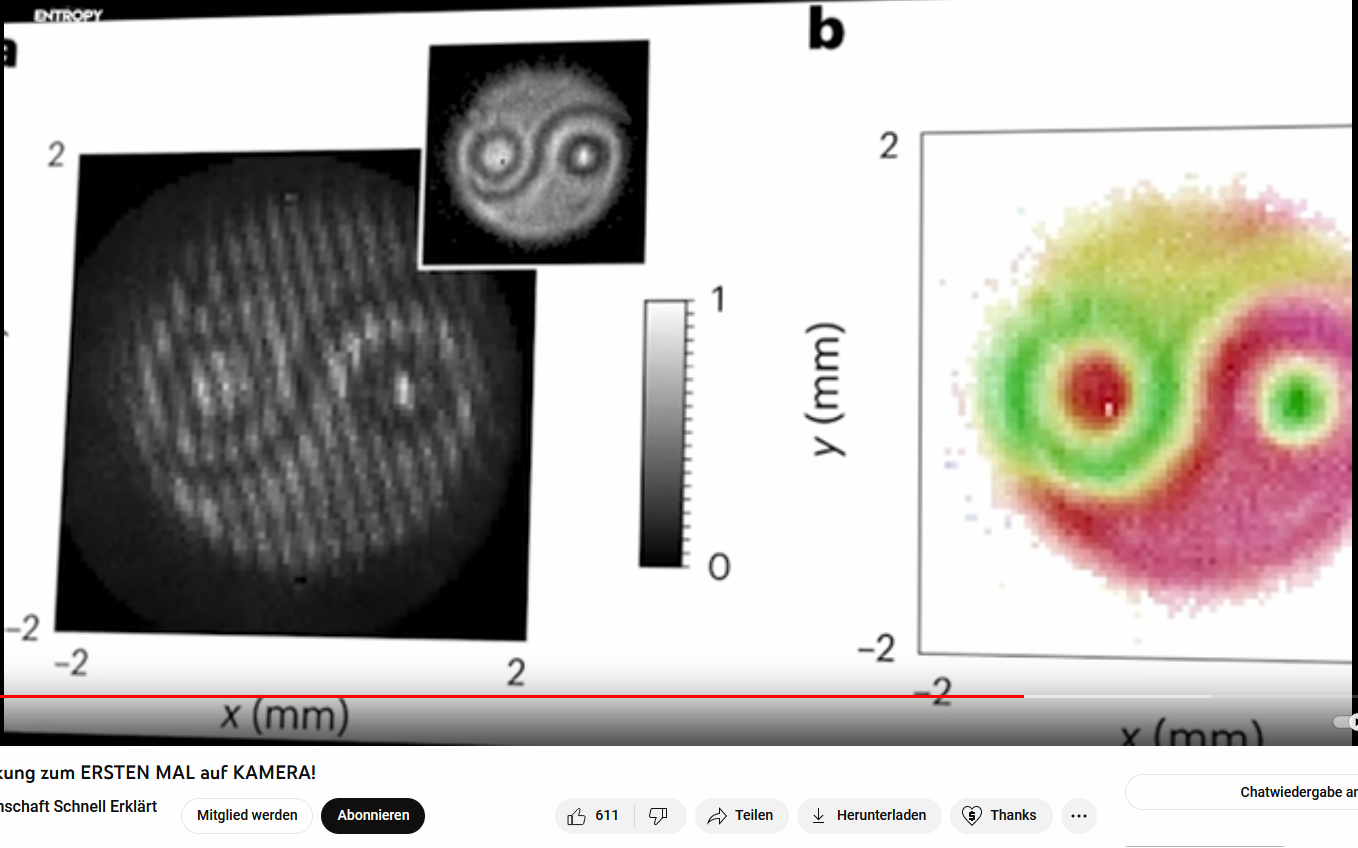

Quantum

Reality

This refers to the realm of existence that is governed by the

principles of quantum mechanics. At this level, particles can exist in multiple

states simultaneously / superposition, objects can be entangled such that the

state of one instantaneously affects the state of another no matter the distance

(quantum entanglement), and particles can tunnel through barriers that they

shouldn't be able to pass through according to classical physics (quantum

tunneling).

Natural

Constants and Laws of Nature

These are the fundamental principles that

dictate the behavior of the universe. They include things like the speed of

light in a vacuum, the gravitational constant, Planck's constant, and the laws

of thermodynamics. These laws and constants are universal and unchanging, and

they provide the foundation for our understanding of the physical world.

Abstract

Entities

These include mathematical objects like numbers and

geometrical shapes, logical constructs, and possibly universals or forms (if one

subscribes to a Platonic or Aristotelian view of metaphysics). These objects

don't exist in physical space and time, but they are integral to our

understanding of the world and provide the basis for logical reasoning and

mathematical calculations.

Consciousness

and Subjective Experience

This level refers to our own personal

experiences and perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and sensations. This is the

realm of existence that we know most directly, because we experience it from a

first-person perspective. It is also the most mysterious, because we don't yet

fully understand the nature of consciousness or how it arises from physical

processes in the brain.

Cultural

and Social Reality

This level includes the shared beliefs, customs,

practices, and institutions of human societies. These are real in the

sense that they shape our behavior and our experiences, but they are not

physical objects and can't be studied in the same way as physical phenomena.

...and beyond:

Transcendental

Reality

In many philosophical and spiritual traditions, there is a

belief in a reality that transcends the physical world and the everyday

experiences of conscious beings. This could be thought of as a divine realm, a

spiritual plane, the ground of being, or the ultimate reality. This level is

often associated with religious and spiritual experiences and is generally

considered to be beyond the reach of empirical scientific methods.

0.2.4. Levels of Nothingness

Similarly,

the ladder of potentialities from Being to Not-Being can be viewed as

subtractive from the aspect of the content of Nothingness.

A

„lifelong passion“ for the ultimate questions of existence led

Robert

Lawrence Kuhn to produce a series of (> 4,000!) in-depth interviews on

these and other topics with experts in television series

→

www.closertotruth.com with:

Why is there Something rather than Nothing? in: Closer To Truth, 2000 ff.:

→ Pillar Cosmos

→ Themes Mystery of Existence

→ Topics + Series Why Anything at all?

→ Why

is There 'Something' Rather Than 'Nothing'? 1,2, Why Not Nothing 1.2, Why is

There Anything at All? 1-4:

We use

the 7 (8) levels in Kuhn's overview article as a short introduction to the wondrous intermediate realm of

potentialities, this...

The Twilight Zone of Beingness and Nothingness

|

1. Nothing as existing space and time that

just happens to be totally empty of all

visible objects (particles and energy are permitted) – an

utterly simplistic, pre-scientific view.

2. Nothing as existing space and time that

just happens to be totally empty of all matter (no

particles, but energy is permitted – flouting the law of mass-energy

equivalence).

3. Nothing as existing space and time that

just happens to be totally empty

of all matter and energy.

4. Nothing as existing space and time that is

by necessity – irremediably and permanently in all

directions, temporal as well as spatial – totally empty of all matter

and energy.

5. Nothing of the kind found in some

theoretical formulations by physicists, where, although

space-time (unified) as well as mass-energy (unified) do not exist,

pre-existing laws, particularly laws of quantum mechanics, do exist.

And it is these laws that

make it the case that universes can and do, from time to time,

pop into existence from “Nothing,” creating spacetime as well as

mass-energy. (It is standard physics to assume that empty space must

seethe with virtual particles, reflecting the uncertainty principle

of quantum physics, where particle-antiparticle pairs come into

being and then, almost always, in a fleetingly brief moment,

annihilate each other.)

6. Nothing where not only is there no

space-time and no mass-energy, but also there are no preexisting laws of physics

that could generate space-time or mass-energy (universes).

7. Nothing where not only is there no

space-time, no mass-energy, and no pre-existing laws of physics, but

also there are no non-physical things or

kinds that are concrete (rather than abstract) – no

Creator, no Creators, and no consciousness (cosmic or otherwise).

This means that there are no physical or non-physical beings or

existents of any kind – nothing, whether natural or supernatural, that

is concrete (rather than abstract).

8. Nothing where not only is there none of the

above (so that, as in Nothing 7, there are no concrete existing

things, physical or non-physical), but also there are no abstract objects of any kind

– no

numbers, no sets, no logic, no general propositions, no universals,

no Platonic forms (e.g., no value).

9. Nothing where not only is there none of the

above (so that, as in Nothing 8, there are no abstract objects), but

also there are no possibilities [potentitalities] of any kind

(recognizing that possibilities and abstract objects overlap, though

allowing that they can be distinguished).

a. Kuhn, SKEPTIC MAGAZINE

18,2 2013

Essentially, the subtypes in

levels 6, 7, and 8 are still to be distinguished:

-

In the objective reality:

in our physical universe and its natural laws

- In our subjective reality:

as consciousness, mind, sentient beings. |

The Way to Absolute

Nothingness

|

Absolute

Emptiness

This concept, most associated with Buddhist philosophy,

refers to the idea that all phenomena, including all of the levels of being

listed above, are void of inherent existence or self-nature. This does not mean

that phenomena do not appear or function; rather, it means that they are

dependently originated and do not exist independently.

Total Non-existence

It's a difficult

concept to grasp because it's not something we can experience or observe. It's

the absence of all things, all existence, all thought, all consciousness, and even the absence of emptiness itself

- in short, the complete absence of

being. Some philosophical and cosmological discussions involve this concept,

especially when discussing the origins of the universe or the nature of

existence itself. Different interpretations underscore how challenging it is to

discuss absolute nothingness, and they vary widely based on cultural,

philosophical, and temporal contexts. The common thread, however, is the

recognition of the paradox inherent in attempting to understand non-existence,

given that our entire perception of reality is predicated upon existence. The

Daodejing speaks of non-being and being arising from the same source,

hinting at a form of nothingness that isn't absolute non-existence, but rather

the state from which existence arises.

Absolute

Nothingness

Or mere nothingness (nihil

simpliciter): this is a modal term in the metaphysics and theology of

creation of John Duns Scotus (1266-1308), which refers to

non-existent things that cannot possibly exist, not even as being in the mind

alone. As

absolutely void Duns Scotus refers to so-called

incompossibilia, fictitious objects (figments) whose essential

form would be a combination of mutually incompatible components,

which cannot even be brought together mentally to form an object,

and are therefore in principle not causable. Incompossibilia

are therefore impossible not only in relation to others (certain

circumstances, existing objects, or the will of a Creator), but also

according to their own form of being, which is why Duns Scotus

speaks of a formal impossibility (i.e. an impossibility according to

form) and of a nihil simpliciter, i.e. a

nothing-simply-thereunto (instead of a nothing-relative-to-other).

This excludes their being in themselves, their being real as well as their being

possible, and consequently their contradiction-free thinkability.

Key differences that distinguish the

idea of Absolute Nothingness from other concepts of Nothing are:

-

Lack

of Properties or Attributes: Most concepts or ideas

have some defining properties or attributes. However, Absolute

Nothingness, by definition, lacks any such properties or

attributes. It is devoid of characteristics, qualities,

substance, energy, space, time, thought, or consciousness.

-

Absence

of Existence: All concepts, ideas, and entities we can

think of exist in some form, whether physically, conceptually,

or subjectively. Absolute Nothingness, however, implies the

absence of any form of existence.

-

Impossibility

of Experience or Observation: We can experience or

observe almost all phenomena, objects, or ideas in some way.

Absolute Nothingness, on the other hand, cannot be experienced

or observed because it implies the non-existence of observers,

observation, or any phenomenon to be observed.

-

Defies

Conventional Understanding and Language: All other

concepts fit within our understanding of reality and language,

but Absolute Nothingness does not. It is not merely a vacuum,

emptiness, or darkness; it's the absence of existence itself,

something our brains, rooted in existence, find difficult to

process or express.

-

Paradoxical

Nature: Trying to understand or describe Absolute

Nothingness is paradoxical because the act of conceptualizing it

gives it a form of existence, contradicting its definition. The

concept inherently challenges our traditional laws of logic and

understanding.

-

Philosophical

and Metaphysical Implications: Unlike most other

concepts, the idea of Absolute Nothingness has profound

philosophical and metaphysical implications. It's intimately

connected with deep questions about the origin of the universe,

the nature of existence, and the limits of human knowledge and

comprehension.

|

0.3. Basic Terms of the Philosophy of Reality

Nothingness as Void

or Emptiness can also be seen as a source of Potentiality, as a creative

ground from which new things or ideas can emerge. It is linked to the concept of

creatio ex nihilo, the idea that creation can arise from nothing.

-

Ontological

Pluralism

-

Concreteness

and Abstractness

-

Contingency

and Necessity

-

Possible

Worlds + Probabilistic Explanation

-

The

Possibility of Nothing

-

Gradation of

Being

-

Metaphysical

Nihilism + Subtraction Arguments

-

Ontology of

the Many

-

The

Principle of Sufficient Reason

-

The grand

Inexplicable

-

Ultimate

Naturalistic Causal Explanations

-

Complete

Explanation of Everything

-

Conceiving

Absolute Greatness

0.3.1. Ontological Pluralism

Ontological pluralism proposes that there are

multiple ways to understand reality, with diverse ontologies capturing distinct

perspectives. It challenges the idea of a single unified framework and

recognizes the importance of diverse knowledge domains. It emphasizes respecting

ontological diversity, promoting interdisciplinary dialogue, and acknowledging

that different ontologies are needed to grasp the complexity of reality.

Ontological

pluralism is a philosophical concept that suggests there are multiple ways of

understanding and describing reality. It posits that there are multiple

ontologies or fundamental categories of existence, each capturing a distinct

aspect or perspective of reality. According to ontological pluralism, reality is

not singular or homogeneous but rather composed of diverse and irreducible

ontological domains.

This

perspective challenges the idea that there is a single, unified framework or

ontology that can explain all aspects of reality. Instead, it acknowledges that

different domains of knowledge, such as the natural sciences, social sciences,

humanities, and spiritual or religious perspectives, offer distinct ways of

understanding reality.

Ontological

pluralism emphasizes the importance of recognizing and respecting the diversity

of ontologies and the various perspectives they offer. It encourages

interdisciplinary dialogue and an open-minded approach to different ways of

knowing. Rather than seeking to reduce all phenomena to a single explanatory

framework, ontological pluralism acknowledges that different ontologies may be

necessary to adequately capture the complexity and diversity of reality.

0.3.2.

Concreteness and Abstractness

The

distinction between concreteness and abstractness in ontology is essential for

understanding the diverse modes of existence in the world. Concreteness refers

to tangible, individual entities with physical properties, while abstractness

refers to conceptual, non-physical entities. Concrete entities are experienced

through the senses, while abstract entities exist as concepts or mental

constructs. The concepts exist on a spectrum, and some entities can possess both

concrete and abstract aspects.

„Der

Begriff des Seienden ist selbst etwas Seiendes.“

(„The concept of being is itself something that exists.“)

Schelling, (Lectures to the)

Philosophy of Revelation

The distinction between concreteness and

abstractness in ontology is crucial for understanding the different modes of

existence and the nature of entities in the world. It highlights the

diversity and complexity of reality, encompassing both the physical and

observable aspects as well as the conceptual and intellectual dimensions of

existence. Philosophical debates surrounding concreteness and abstractness

involve discussions about the nature of universals, the relationship between

mind and reality, and the nature of knowledge and understanding.

Concreteness and abstractness are key

concepts in ontology, the branch of philosophy concerned with the study of

being, existence, and the nature of

reality. They describe different modes of

existence or ways in which entities or concepts can be understood.

Concreteness refers to the quality

of being tangible, particular, or individual. Concrete entities are those

that have a physical or material existence and can be experienced through the

senses. Examples of concrete entities include physical objects like trees,

animals, and buildings, as well as specific events or occurrences.

Concrete entities are typically

characterized by their spatiotemporal location, their ability to interact

causally with other entities, and their potential to be perceived or directly

experienced. They possess specific properties and characteristics that can be

observed or measured.

On the other hand, abstractness

refers to the quality of being conceptual, general, or non-physical.

Abstract entities are not directly perceptible through the senses and do not

have a material or spatiotemporal existence. Instead, they exist as concepts,

ideas, or mental constructs.

Abstract entities include concepts such as

numbers, mathematical equations, logical principles, moral values, and

philosophical ideas. They are typically characterized by their generality,

universality, and the fact that they can be shared and understood by multiple

individuals.

Abstract entities often lack concrete

physical properties and cannot be located in space or time. They are not subject

to direct empirical observation but can be studied through logical analysis,

reasoning, and conceptual understanding. Abstract entities are often seen as

products of human thought and language.

It's important to note that concreteness

and abstractness exist on a spectrum rather than being strictly dichotomous.

Some entities or concepts may possess both concrete and abstract aspects. For

example, while the concept of „justice“ is considered abstract, its

manifestations and applications in specific legal cases can have concrete and

tangible effects.

0.3.3.

Contingency and

Necessity

Contingency and necessity in ontology raise

questions about causality and the fundamental nature of reality. Contingency

refers to entities that rely on external factors, while necessity refers to

entities that exist inherently. Contingent entities depend on specific

circumstances or causes, while necessary entities exist in all possible worlds.

These concepts help us understand the nature of existence and the relationships

between entities. Contingency and necessity exist on a spectrum, and some

entities may have aspects of both. They are interconnected concepts that explore

the nature of reality and existence.

The

exploration of contingency and necessity in ontology raises questions about the

nature of causality, the limits of explanation, and the fundamental nature of

reality. It informs discussions on topics such as the existence of a

Creator, the nature of universals, and the nature of logical truths. Different

philosophical perspectives and traditions offer various interpretations and

perspectives on the nature and extent of contingency and necessity in the

ontology of entities. Contingency and necessity are fundamental concepts in

ontology that describe different modes of existence or ways in which

entities can exist.

Contingency

refers to the property of being dependent on something else for its existence

or occurrence. A contingent entity is one that could have been different or

could have failed to exist altogether. Its existence or properties are not

logically necessary or self-explanatory.

Dependence is the notion that certain entities or states of affairs rely on

or require the existence or contribution of other entities for their own

existence or intelligibility. It implies that some things are

not

self-sufficient or self-explanatory but instead depend on external factors,

causes, or conditions.

For instance, an effect depends on its cause, a building depends

on its constituent materials, and an event depends on a variety of causal

factors.

Contingent

entities are characterized by their reliance on external factors, causes, or

conditions. They are subject to change and are contingent upon specific

circumstances or causal factors. For example, the existence of a particular

individual, the occurrence of a specific event, or the presence of a certain

object in a given location can be considered contingent.

In other words, contingent entities are those whose existence or properties

are not logically required or essential.

Necessity,

on the other hand, refers to the property of being logically required and

unavoidable. A necessary entity is one that exists or must exist in all

possible worlds and cannot fail to exist. Its existence or properties are not

contingent upon external factors or conditions but are inherent and

self-explanatory. Necessary entities are independent of specific circumstances

or causal factors. They are considered essential or indispensable and do not

rely on external causes for their existence. For example, mathematical

truths, such as the fact that 2+2=4, are often regarded as necessary because

they hold true in all possible worlds.

The concepts of contingency and necessity are closely related and provide a

framework for understanding the nature of existence and the relationships

between entities in ontology. They help distinguish between entities that are

dependent on external factors and those that possess inherent and

self-explanatory existence.

It is

worth noting that contingency and necessity exist on a spectrum rather than

being absolute categories. Some entities may have aspects of both

contingency and necessity. For example, while the existence of an individual

person might be contingent upon various factors such as their parents, the

existence of the concept of personhood itself may be regarded as necessary due

to its universality and conceptual indispensability.

Contingency, dependence, and the

ontology of the many are interconnected philosophical concepts that explore

the nature of existence, the relationship between entities, and the fundamental

constituents of reality.

0.3.4.

Possible Worlds

+ Probabilistic Explanation

The

probabilistic explanation suggests that the existence of the universe may be a

result of random or probabilistic processes. It explores the idea that the

conditions for a universe to arise with its particular laws and structures

aligned by chance. This perspective considers fundamental laws like quantum

mechanics as providing a basis for indeterminism and randomness. However, it is

important to note that this explanation is speculative and philosophical,

lacking empirical evidence. The question of why there is something rather than

nothing remains a profound mystery and subject of ongoing inquiry.

The

probabilistic

explanation

of why there is something rather than nothing is a speculative

and philosophical attempt to address the question of why the universe exists or

why there is a reality rather than an absolute nothingness. It explores the

possibility that the existence of the universe is a result of random or

probabilistic processes.

According

to this perspective, the emergence of the universe could be seen as a chance

occurrence governed by probabilistic principles. It suggests that within the

vastness of all possible configurations of existence, the conditions for a

universe to arise with its particular laws, constants, and structures

happened to align in a way that allowed for the development of complex systems,

including life.

In a

probabilistic framework, the fundamental laws of nature, such as quantum

mechanics, could be seen as providing a basis for indeterminism and randomness

at a fundamental level. Random fluctuations or quantum events could have

played a role in initiating the universe or determining its initial conditions.

It's

important to note that the probabilistic explanation is speculative and

philosophical in nature. It does not provide a definitive or scientific

explanation supported by empirical evidence. The question of why there is

something rather than nothing remains one of the deepest and most profound

mysteries of existence, and it continues to be a subject of philosophical and

scientific inquiry.

0.3.5. The Possibility

of Nothing

The

possibility of nothing in ontology examines whether a state of absolute absence

of entities, properties, and relations is conceivable. It raises philosophical

debates about the coherence of nothingness as a concept and its potential as a

genuine state. The topic also relates to the nature of existence, the origins of

reality, and the reasons for why something exists instead of nothing. Different

arguments and positions exist regarding the possibility of nothing, considering

contingent and necessary entities, as well as cosmological and metaphysical

perspectives. It's a complex topic influenced by diverse philosophical,

scientific, and cultural viewpoints.

Das „Bewußtseyn, daß das Nichtseyn dieser

Welt ebenso möglich sei, wie ihr Daseyn“,

= The „consciousness

that the non-being of this world is just as possible as its being“,

Die Welt ...

„als

Etwas, dessen Nichtseyn nicht nur denkbar,

sondern sogar ihrem Daseyn vorzuziehen wäre.“

= The world ... „as

something whose non-being would not only be conceivable,

but even preferable to its being“.

Arthur

Schopenhauer

„Die

Welt als Wille und Vorstellung“.

Einstein's favorite philosopher!

The

possibility of Nothing in ontology refers to the question of whether there could

have been a state of affairs in which there is an absence of all entities,

properties, and relations. It involves exploring the concept of nothingness and

examining whether it is a genuine possibility or a mere conceptual

abstraction.

In

ontological discussions, Nothing refers to a state devoid of any existence,

including physical objects, properties, events, and even abstract entities.

It represents a complete absence of being or a complete lack of ontological

entities.

The

possibility of nothing in ontology raises several philosophical questions and

debates. One of the central questions is whether nothingness is a coherent

concept. Some argue that since nothingness lacks any properties or

characteristics, it cannot be conceived or talked about meaningfully. They

assert that the notion of nothingness is merely a conceptual placeholder,

representing the absence of something rather than an actual state.

Others

argue that nothingness is a genuine possibility that can be meaningfully

considered. They argue that if there is something, it is conceivable that there

could have been nothing instead. This perspective suggests that nothingness

is a potential state of affairs that could have obtained or could

potentially obtain.

Another

dimension of the possibility of nothing in ontology relates to the nature of

existence itself. It raises questions about the nature of reality, the

origins of existence, and the fundamental principles that govern being.

Exploring the possibility of nothing prompts reflection on whether there could

be a reason or explanation for why there is something rather than nothing.

Philosophers

have proposed various arguments and positions on the possibility of nothing in

ontology. Some argue that the very existence of contingent entities suggests

that nothingness is not a necessary state, as it is always possible for

contingent entities to fail to exist. Others contend that the existence of

necessary entities, such as mathematical truths or logical principles,

suggests that nothingness is not a possibility, as there are certain aspects

of reality that must exist.

Additionally, the possibility of nothing in ontology intersects with

cosmological and metaphysical debates about the nature of the universe and

the existence of a necessary being or ultimate reality. It is connected to

discussions on the nature of causality, the principles of explanation, and the

boundaries of human understanding.

It's

important to note that the possibility of nothing in ontology is a complex and

challenging topic. Different philosophical perspectives, scientific insights,

and cultural and religious beliefs influence the understanding and

interpretation of this concept. The exploration of the possibility of nothing

continues to provoke thought-provoking discussions and deepens our understanding

of the nature of existence and the boundaries of ontology.

0.3.6. Gradation of

Being

The

Gradation of Being is a concept in medieval philosophy that describes a

hierarchical scale of existence, ranging from lower forms to higher, more

complex forms. Reality is seen as diverse, with varying degrees of perfection.

Inanimate objects occupy the lowest level, followed by increasingly complex

entities such as plants, animals, humans, and ultimately, spiritual or divine

beings. Each level derives its existence from the one above it, and higher

levels possess greater perfections. The concept is associated with thinkers like

Thomas Aquinas and explains the relationship between Creator, creation, and

different levels of being. Interpretations may vary among philosophers and

traditions.

The

Gradation of Being is a concept that originates from medieval philosophy and

metaphysics, particularly within the framework of Scholasticism. It

refers to the idea that there exists a hierarchical or graded scale of

existence or being, ranging from the lowest and simplest forms of existence

to the highest and most complex.

According

to this concept, reality is not uniform or homogeneous but rather exhibits

varying degrees of perfection, with each level building upon and surpassing the

previous one. This gradation is often depicted as a scale or ladder, with

different levels representing different degrees of being or reality.

At

the lower end of the scale, you might find inanimate objects or entities

with minimal capacities for existence, such as rocks or minerals. As you ascend

the scale, you encounter increasingly complex forms of being, including plants,

animals, and humans. Finally, at the highest end of the gradation, you may find

spiritual or divine entities, representing the pinnacle of existence.

The

gradation of being implies that reality is structured in a hierarchical manner,

with each level or degree of being participating in and deriving its existence

from the level above it. The concept also implies that the higher levels of

being possess greater perfections or qualities than the lower levels.

The

notion of the Gradation of Being is associated with philosophers like Thomas

Aquinas, who integrated Aristotelian metaphysics with Christian theology. It

served as a framework to explain the diversity and hierarchy of existence and to

explore the relationship between Creator, creation, and the various levels of

being.

It's

important to note that interpretations and understandings of the Gradation of

Being may vary among different philosophers and philosophical traditions.

0.3.7. Metaphysical

Nihilism + Subtraction Arguments

Metaphysical nihilism challenges the existence of

any fundamental reality and argues that all entities lack objective existence.

Subtraction arguments support this view by showing that the removal of entities

or aspects of reality does not lead to contradictions. These arguments examine

different aspects of reality, such as physical objects and abstract entities,

demonstrating their dispensability. Proponents extend subtraction arguments to

properties, relations, and consciousness, aiming to negate the need for a

fundamental reality. Metaphysical nihilism is controversial, and critics argue

it oversimplifies reality and fails to address its complexity. The debate

surrounding metaphysical nihilism and subtraction arguments continues.

Metaphysical

nihilism is a philosophical stance that challenges the existence of any

fundamental or ultimate reality. It argues that there is no underlying

essence, substance, or universal principle that gives rise to or governs the

nature of existence. According to metaphysical nihilism, all purported entities,

concepts, or aspects of reality lack objective or independent existence.

Subtraction arguments

typically

proceed by examining different aspects of reality and demonstrating that their

removal does not lead to any inconsistencies or contradictions. By

systematically subtracting various entities or properties, proponents of

metaphysical nihilism argue that we can ultimately arrive at a state of absolute

nothingness or nonexistence without encountering any logical problems

For

example, a subtraction argument might begin by considering physical objects. It

could argue that if we were to subtract all physical objects from

existence, there would be no inherent contradiction or logical inconsistency.

The argument may then proceed to consider abstract entities, such as numbers or

mathematical truths, and propose that their subtraction would similarly not

result in any contradictions.

Furthermore,

proponents of metaphysical nihilism might extend subtraction arguments to

include other aspects of reality, such as properties, relations, concepts,

and even consciousness. The goal is to show that at every level, the removal

of entities or aspects of reality does not give rise to any logical or

conceptual problems.

Subtraction

arguments for metaphysical nihilism are often intended to challenge the

assumption that there must be a fundamental or ultimate reality underlying all

existence. By demonstrating that all purported aspects of reality can be

conceptually subtracted without contradiction, metaphysical nihilists argue that

there is no need to posit the existence of any fundamental entities or

ultimate reality. It is worth noting that metaphysical nihilism is a highly

controversial position, and subtraction arguments have been subject to

criticism and debate. Critics may argue that subtraction arguments rely on

overly simplistic or reductionist understandings of reality, or that they

fail to adequately address the complex nature of existence. As with many

philosophical positions, the debate surrounding metaphysical nihilism and its

supporting arguments remains ongoing.

0.3.8. Ontology of the

Many

The

ontology of the many asserts that reality consists of multiple fundamental

entities instead of a single substance. It highlights the importance of

relations, interactions, and composition in understanding reality. This

perspective acknowledges the contingency and dependence of entities, emphasizing

their diversity and complexity. The exploration of contingency, dependence, and

the ontology of the many is essential in metaphysics to understand being and

causality. Different philosophical traditions contribute to ongoing debates in

metaphysics and ontology.

Nothing

is pleasant that is not spiced with variety.

Francis Bacon,

Essays

The ontology of the many is a metaphysical position that posits

that

reality

consists of a plurality of fundamental entities or elements rather than a

single, unified substance or entity.

It challenges the notion of a singular, all-encompassing

substance and suggests that the diversity and complexity of reality arise from

the interaction and combination of many distinct entities or individuals. This

perspective often emphasizes the importance of relations, interactions, and the

composition of entities as crucial aspects of understanding the nature of

reality.

When

considered

together, these concepts suggest that existence is not uniform or self-contained

but rather characterized by contingency and dependence.

Entities or

states of affairs are contingent because they could have been

different or non-existent, and they are

dependent because they rely on other entities or

conditions for their existence or intelligibility.

The

ontology of the many extends this understanding by emphasizing

that reality is composed of a multitude of distinct entities,

each with its own characteristics and interrelations. These entities contribute

to the complexity and diversity of existence and challenge the idea of a

singular, monolithic substance or entity underlying all of reality.

The

exploration of contingency, dependence, and the ontology of the many is

fundamental to metaphysics and the understanding of the nature of being,

causality, and the relationships between entities in the fabric of reality.

Different philosophical traditions and thinkers offer various

interpretations and perspectives on these concepts, leading to ongoing debates

and discussions in metaphysics and ontology.

0.3.9. The Principle of

Sufficient Reason

The

Principle of Sufficient Reason (PSR) states that everything in the universe has

a reason or explanation for its existence, and nothing happens without a cause.

It reflects the belief in an ordered and intelligible world governed by logical

and causal principles. The PSR has influenced various areas of philosophy and

has been used to argue for the existence of a Creator, although critics have

raised objections to its applicability and potential infinite regress.

The Principle of Sufficient

Reason (PSR) is a philosophical principle that aims to establish that

everything in the universe has a reason or explanation for its existence,

properties, and characteristics. It asserts that nothing is random or

arbitrary but instead operates within a framework of logical principles and

causal connections.

The PSR suggests that

every event or entity, from the smallest particles to the largest cosmic

phenomena, has a sufficient reason for its occurrence or existence. This

reason could be a causal explanation, a logical necessity, or some other form of

explanation. According to the PSR, nothing simply happens without a cause or

without being grounded in some underlying principle.

The principle can be seen as

a rationalist stance, rooted in the belief that the world is ordered and

intelligible. It assumes that there are underlying laws or principles that

govern the behavior of the universe, making it predictable and understandable.

By seeking explanations for phenomena, the PSR promotes the idea that the world

is not chaotic or arbitrary but instead adheres to a rational and coherent

structure.

The PSR has been influential

in various areas of philosophy, including metaphysics, epistemology, and the

philosophy of science. It has been used to argue for the existence of a

Creator, as proponents claim that the PSR requires a sufficient reason for

the existence of the universe itself. Critics, on the other hand, have

raised objections to the PSR, questioning its applicability to certain realms

of knowledge or arguing that it leads to an infinite regress of explanations.

0.3.10. The Grand

Inexplicable

The Principle of Sufficient

Reason (PSR) encounters difficulties when confronted with the grand

inexplicable, which refers to questions about the existence of the universe,

fundamental laws, and the ultimate foundation of reality. Some philosophers

argue that certain aspects of reality may be ultimate or foundational, resisting

complete explanation. This tension raises the possibility of limits to our

rational understanding and the existence of unexplained truths. The challenge of

reconciling the PSR and the grand inexplicable continues to be a topic of debate

in metaphysics and philosophy of science.

The

PSR faces challenges when it comes to accounting for what is often referred to

as the grand

inexplicable or the ultimate foundation of reality.

The grand

inexplicable represents the question of why there is something rather than

nothing, why the universe exists at all, or why there are

certain fundamental laws and principles governing the cosmos.

These questions push the limits of explanation and challenge the

idea that everything can be accounted for by appealing to prior causes or

reasons.

In

the face of the grand inexplicable, some philosophers argue that the

PSR

may need to be limited or modified.

They suggest

that there might be certain aspects of

reality that are ultimate or foundational,

which cannot be further explained or reduced to other factors.

These foundational aspects might include

the

existence of the universe itself, the nature of fundamental laws, or the

principles that underlie reality.

Thus,

while the PSR posits that everything must have an explanation, the grand

inexplicable raises the possibility that there may be fundamental aspects of

reality that defy complete explanation. It acknowledges that there may be limits

to our rational understanding and that

there may

exist truths or principles that are simply part of the fabric of existence

without further explanation.

The

tension between the PSR and the grand inexplicable highlights the philosophical

challenge of comprehending

the ultimate nature of reality and the

limits of human reason.

It remains a topic of ongoing debate and exploration within

metaphysics and philosophy of science.

0.3.11. Ultimate

Naturalistic Causal Explanations

Ultimate naturalistic causal

explanations aim to provide foundational explanations for fundamental aspects of

reality within a naturalistic worldview. These explanations trace phenomena to