# 559 © Hilmar

Alquiros, Philippines

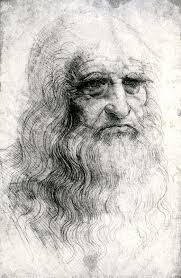

Leonardo da Vinci's Wisdom.

“Every part is disposed to unite with the

whole,

that it may thereby

escape from its own incompleteness.”

Prologue:

"That which is termed nothingness is found only in time and speech. In time it is found between the past and the future and retains nothing of the present; in speech likewise when the things spoken of do not exist or are impossible. In the presence of nature nothingness is not found: it has its associates among the things impossible whence for this reason it has no existence.

With regard to time, nothingness lies between the past and the future, and has nothing to do with the present, and as to its nature it is to be classed among things impossible: hence, from what has been said, it has no existence; because where there is nothing there would necessarily be a vacuum. cf. No. 916.

Among the great things which are found among us the existence of Nothing is the greatest. This dwells in time, and stretches its limbs into the past and the future, and with these takes to itself all works that are past and those that are to come, both of nature and of the animals, and possesses nothing of the indivisible present. It does not however extend to the essence of anything. c.a. 398 v. d.

Amid the immensity of the things about us the existence of nothingness holds the first place, and its function extends over the things that have no existence, and its essence dwells in respect of time between past and future, and possesses nothing of the present.

This nothingness has the part equal to the whole and the whole to the part, the divisible to the indivisible, and its power does not extend among the things of nature, for inasmuch as this abhors a vacuum this nothingness loses its essence because the end of one thing is the beginning of another. And it comes to the same amount whether we divide it or multiply it or add to it or subtract from it, as is shown by the arithmeticians in their tenth sign which represents this nothingness [zero]. And its power does not extend among the things of nature. b.m. 131 r.

Nothingness has a surface in common with a thing and the thing has a surface in common with nothingness, and the surface of a thing is not part of this thing. It follows that the surface of nothingness is not part of this nothingness; it must needs be therefore that a mere surface is the common boundary of two things that are in contact; thus the surface of water does not form part of the water nor consequently does it form part of the atmosphere, nor are any other bodies interposed between them. What is it therefore that divides the atmosphere from the water? It is necessary that there should be a common boundary which is neither air nor water but is without substance, because a body interposed between two bodies prevents their contact, and this does not happen in water with air because they are in contact without the interposition of any medium.

Therefore they are joined together and you cannot raise up or move the air without the water, nor will you be able to raise up the flat thing from the other without drawing it back through the air. Therefore a surface is the common boundary of two bodies which are not continuous, and does not form part of either one or the other for if the surface formed part of it it would have divisible bulk, whereas however it is not divisible and nothingness divides these bodies the one from the other. b.m. 159 v."

Leonardo da Vinci’s reflections on nothingness reveal a profound understanding of the abstract and paradoxical nature of time, space, and existence. He describes nothingness not merely as an absence of things but as an integral part of our perception of reality. Interestingly, Leonardo situates nothingness in time and speech, emphasizing that it occupies the void between the past and the future but never touches the present. This is a powerful metaphor for human consciousness and existence—nothingness is where we are constantly situated, always between what has been and what is to come, yet never fully embracing the fleeting present moment.

In his discussions of nature, Leonardo makes it clear that nothingness has no place in the physical world. For him, nature abhors a vacuum, and the existence of nothingness is only conceptual—it belongs to the realm of impossibilities. This echoes ancient philosophical debates about the existence of a void, particularly those of the Greek philosophers like Parmenides and Aristotle, who argued against the notion of a vacuum in nature. Leonardo’s approach, however, is more mathematical, as he links nothingness to the concept of zero, indicating its functional role in human knowledge but nonexistence in the physical realm.

Leonardo’s idea of nothingness being divisible to infinity but never having substance is also a brilliant reflection on mathematics and metaphysics. The boundary he describes between water and air—a surface that is neither part of water nor air—points to a deeper meditation on the limits of perception. It suggests that the line between something and nothing, much like the edge of an idea, is delicate and elusive, but crucial. It’s this boundary that challenges the very nature of reality and perception, bringing to mind modern explorations of quantum physics where particles can seem to exist and not exist simultaneously.

Finally, his

statement that "nothingness has a surface in common with a thing"

demonstrates Leonardo’s philosophical depth. He seems to suggest that

existence and nonexistence are two sides of the same coin.

The way he examines the interaction between bodies and the spaces they

occupy speaks to a timeless inquiry into the nature of being—a question

still debated by philosophers and scientists alike.

Leonardo’s contemplations on nothingness offer us a window into his dual identity as both a scientist and a philosopher. His ability to cross the boundaries of empirical observation and metaphysical speculation makes these reflections particularly rich. Here, nothingness is not merely an absence but an essential part of the fabric of reality, guiding both the natural world and the human mind. This positions Leonardo not only as an artist and inventor but as a thinker who engaged deeply with some of the most difficult and abstract questions of existence.

Leonardo's Wisdom

Philosophy

-

It is possible to conceive everything that has substance as divisible into an infinite number of parts.

-

Nature is full of infinite causes which were never set forth in experience!

-

Supreme happiness will be the greatest cause of misery, and the perfection of wisdom the occasion of folly. c.a. 39 v. c

-

The age as it flies glides secretly and deceives one and another; nothing is more fleeting than the years, but he who sows virtue reaps honor. c.a. 71 v. a

-

The sexual drive to procreate is channeled into creativity. -D

-

Life well spent is long.

-

As a well-spent day brings happy sleep, so life well used brings happy death. Tr. 28 a

-

Nothingness has no centre, and its boundaries are nothingness. My opponent says that nothingness and a vacuum are one and the same thing. c.a. 289 v. b

-

Intellectual passion drives out sensuality. c.a. 358 v. a

-

The soul can never be infected by the corruption of the body, but acts in the body like the wind which causes the sound of the organ. Tr. 71 a

-

O mathematicians, throw light on this error.

-

The thoughts turn towards hope. 1 c.a. 68 v. b

-

Reprove your friend in secret and praise him openly. 1194.

-

Oh! speculators on perpetual motion how many vain projects you have created! 1206.

-

It is easier to resist at the beginning than at the end.

-

For nothing can be loved or hated unless it is first known.

-

Wisdom is the daughter of experience. 1150.

-

Truth alone was the daughter of time. m 58 v.

-

Small rooms or dwellings set the mind in the right path; large ones cause it to go astray. ms. 2038 Bib. Nat. 16 r.

-

Call not that riches which may be lost; virtue is our true wealth. ms. 2038 Bib. Nat. 34 v.

-

Every action done by nature is done in the shortest way. b.m. 85 v.

-

Where the descent is easier there the ascent is more difficult. b.m. 120 r.

Leonardo’s philosophical reflections reveal a mind that sought to understand not only the mechanics of the physical world but also the essence of human existence. He begins with a statement that touches on the infinite divisibility of matter, suggesting that everything with substance can be infinitely divided. This idea mirrors the atomistic theories of Democritus and points forward to later developments in quantum physics, where particles are understood as existing on a spectrum of probabilities rather than as solid, indivisible objects. Leonardo’s brilliance lies in his ability to merge abstract, scientific thought with metaphysical inquiry, probing the limits of human understanding.

His assertion that “nature is full of infinite causes which were never set forth in experience” is both humble and revolutionary. It acknowledges that there are phenomena and forces at work beyond what we can perceive or measure. This resonates with modern scientific inquiry, which continues to uncover layers of complexity in nature that challenge our previous assumptions. Leonardo reminds us that the universe is far vaster than human comprehension can currently grasp.

The observation that supreme happiness leads to misery and the perfection of wisdom to folly reflects Leonardo’s deep understanding of the human condition. This paradox is one that recurs in Stoic and Eastern philosophies: the idea that extremes—whether in joy or wisdom—can lead to their opposites. Leonardo sees the pursuit of absolute ideals as dangerous, warning us of the inherent balance in life. If we aim for the highest forms of happiness or wisdom, we risk becoming disillusioned or detached from reality.

He continues this theme by reflecting on the fleeting nature of time: “The age as it flies glides secretly and deceives one and another; nothing is more fleeting than the years, but he who sows virtue reaps honor.” Leonardo speaks to the impermanence of life and the subtle passage of time that often catches us off guard. His belief in the lasting nature of virtue reflects the humanist tradition, emphasizing that while we cannot stop time, we can act with integrity and honor, leaving behind something enduring. Virtue, in this case, is the antidote to the ephemeral nature of existence.

Leonardo's commentary on the sexual drive being channeled into creativity is a profound psychological insight. He recognizes the transmutation of primal desires into higher forms of expression—a process familiar to Freud’s theory of sublimation centuries later. Here, Leonardo sees the possibility of elevating biological urges into something intellectually and artistically meaningful, demonstrating his belief in the elevating potential of human nature.

The philosophical reflection “life well spent is long” and “as a well-spent day brings happy sleep, so life well used brings happy death” encapsulates Leonardo's views on mortality and purpose. For him, the quality of life is not measured by its length but by how it is lived. This echoes the teachings of Stoicism and Daoism, where a life filled with meaningful action, rather than hedonistic pursuits, results in peace at the end of one’s journey. The metaphor of sleep as a symbol for death is particularly poignant, suggesting that death need not be feared if one has lived fully and well.

In Leonardo’s exploration of nothingness, he returns to his fascination with the void and the impossible. His notion that “nothingness has no center, and its boundaries are nothingness” speaks to his understanding of the limitations of human knowledge. Nothingness, as a concept, pushes the boundaries of thought, leaving behind the safe confines of physical reality and entering the realm of abstract speculation. It is a recurring theme in his work—a reflection of his relentless curiosity about the invisible forces that shape our universe.

Intellectual passion driving out sensuality is yet another of Leonardo’s psychological insights. For him, the pursuit of knowledge and wisdom transcends physical desires. This view ties into his broader belief in human potential: that by focusing on intellectual development, we are capable of rising above the instinctual drives that often dominate our lives. This reinforces the notion that the mind, not the body, is the seat of true power and virtue.

Leonardo’s reflections on friendship and praise—to reprove a friend in secret and praise them openly—echo age-old principles of honor and trust. To criticize someone publicly is a betrayal, while to honor them publicly is a form of generosity and recognition. This simple yet profound wisdom continues to resonate in today’s world, where public criticism dominates, and private virtues go unrecognized.

He then turns his sharp mind to perpetual motion and those who speculate on it, referring to them as creators of vain projects. Here, Leonardo is skeptical of grandiose, impossible endeavors—grounding his philosophy in the limitations of human knowledge and ability. He warns us to be cautious of false promises in both science and life.

In his reflections on truth, Leonardo asserts that wisdom is the daughter of experience—a notion that connects knowledge to practical, lived reality. His statement that “truth alone was the daughter of time” places truth on a higher plane, suggesting that truth reveals itself gradually through time, just as experience leads to wisdom. This offers an elegant reconciliation between intellectual discovery and the passage of time.

Lastly, Leonardo’s musings on virtue and wealth are timeless. “Call not that riches which may be lost; virtue is our true wealth.” In a world obsessed with material wealth, Leonardo reminds us that only virtue is permanent and cannot be taken away. It is a sobering thought and one that continues to be relevant in today’s consumer-driven society. By urging us to cultivate virtue rather than accumulate possessions, Leonardo champions a life of meaning over materialism.

In the end, Leonardo’s philosophical reflections form a cohesive worldview, one that is grounded in both humanistic principles and a keen observation of the natural world. His thoughts transcend time, offering us wisdom that is just as applicable today as it was during the Renaissance. The interplay between time, mortality, human virtue, and the limits of knowledge creates a rich tapestry of ideas that continue to inspire and challenge those who engage with them.

Science

-

Every quantity is intellectually conceivable as infinitely divisible. 1216.

-

Experience, the interpreter between resourceful nature and the human species, teaches that that which nature works out cannot operate in any other way than reason. c.a. 86 r. a

-

There is no result in nature without a cause; understand the cause and you will have no need of the experiment. c.a. 147 v. a

-

Experience is never at fault; it is only your judgment that is in error. c.a. 154 r. h

-

Wrongly do men cry out against experience and with bitter reproaches accuse her of deceitfulness. c.a. 154 r. c

-

There cannot be any sound where there is no movement or percussion of the air. b 4 v.

-

Science, knowledge of the things that are possible present and past; prescience, knowledge of the things which may come to pass. Tr. 46 r.

-

Every action of nature is made along the shortest possible way. Quaderni iv 16 r.

-

The earth is moved from its position by the weight of a tiny bird resting upon it. b.m. 19 r.

-

In rivers, the water that you touch is the last of what has passed and the first of that which comes: so with time present. Tr. 63 a

-

Many times one and the same thing is drawn by two violences, namely necessity and power. Tr. 70 a

-

Every continuous quantity is infinitely divisible; therefore the division of this quantity will never result in a point. b.m. 204 v.

-

Movement is the cause of all life. h 141 [2 v.] r.

-

Science is the captain, practice the soldiers. 1160.

-

The man who blames the supreme certainty of mathematics feeds on confusion. 1157.

-

There is no certainty in sciences where one of the mathematical sciences cannot be applied. 1158.

-

A point is not a part of a line. Tr. 63 a

-

The cause nature produces the effect in the briefest manner that it can employ. b.m. 174 v.

-

The origin of the penis is placed on the pubic bone. it is so supported in order to resist the forces active in coitus. If this bone did not exist these forces would return the penis backwards on meeting resistance, and it would often enter more into the body of the operator than into that of the operated...

Leonardo da Vinci’s reflections on science demonstrate a mind that was not only ahead of his time but also deeply rooted in the principles of observation, logic, and nature. His approach to science is holistic, blending mathematics, physics, and biology, and this is evident in his opening statement: “Every quantity is intellectually conceivable as infinitely divisible.” This ties into the concept of infinity—a theme he frequently explored. Long before modern mathematics formalized the idea, Leonardo intuitively understood that matter and space could be endlessly divided, a concept central to both calculus and quantum mechanics today. In this, Leonardo anticipates the future of scientific inquiry, where the deeper we delve, the more layers we uncover.

His assertion that “experience is the interpreter between resourceful nature and the human species” reveals Leonardo’s respect for empirical knowledge. He saw experience as the bridge between the complexity of nature and the human ability to understand it. This method of learning through observation and experimentation forms the bedrock of modern scientific methodology. He acknowledged that nature operates according to reason, meaning that behind every natural event is a logical explanation, even if it hasn’t been discovered yet.

In his reflection, “there is no result in nature without a cause,” Leonardo strikes at the heart of the scientific principle of causality. To him, understanding the cause is paramount—once the cause is known, there is no need for speculative experiments. This mirrors the modern scientific focus on finding fundamental laws to explain the universe, as seen in fields like physics and chemistry. Leonardo's belief in a cause-and-effect structure in nature underlines his desire for a world understood through reason rather than superstition or guesswork.

Further emphasizing his empirical mindset, Leonardo chides those who blame experience for their misunderstandings: “Experience is never at fault; it is only your judgment that is in error.” Here, he defends the reliability of empirical observation and suggests that human error lies in misinterpretation, not in the observation itself. This idea resonates with modern scientists, who constantly refine their hypotheses and models in the face of new evidence.

His thoughts on sound and movement are equally striking: “There cannot be any sound where there is no movement or percussion of the air.” This simple yet profound statement distills the essence of acoustics—a science still developing during Leonardo’s time. By linking sound to the movement of air, Leonardo highlights the physical properties of sound, anticipating what would later be expanded upon in wave theory.

Leonardo's focus on the economy of nature—“every action of nature is made along the shortest possible way”—speaks to his understanding of efficiency in the natural world. Nature, for Leonardo, operates with minimal waste, a principle that is central to modern physics, particularly in thermodynamics and the laws of motion. The idea of efficiency in nature’s processes mirrors today’s understanding that the universe, governed by physical laws, tends toward states of minimal energy.

In one of his most delicate observations, Leonardo states: “The earth is moved from its position by the weight of a tiny bird resting upon it.” Here, he encapsulates the interconnectedness of all things, from the tiniest creatures to the largest celestial bodies. While the weight of a bird may seem negligible, Leonardo’s statement reflects his understanding of physics and forces, where even small actions have consequences. This ties into the modern principle of gravity, where every object exerts a force on every other object, no matter how small.

The metaphorical reflection on time and rivers—“the water that you touch is the last of what has passed and the first of that which comes: so with time present”—is not only poetic but also encapsulates Leonardo’s grasp of time’s continuity. Just as Heraclitus once remarked that one cannot step into the same river twice, Leonardo reflects on the fleeting nature of the present moment, seeing time as both flowing and eternal. This fluidity of time remains a fascinating concept for modern physics, especially in the realms of relativity and time dilation.

In his observations about motion, Leonardo explores the forces of necessity and power—natural forces that compel matter to move. His insights on the division of quantities and infinite divisibility further underscore his fascination with mathematical principles. He grasps that natural phenomena, down to their smallest parts, can be infinitely divided—a revolutionary concept that resonates in modern theories of space and matter.

Leonardo’s thoughts about the human body are just as profound. His detailed understanding of anatomy is reflected in statements like “the origin of the member is placed on the pubic bone,” a reflection on biomechanics and functionality in human reproduction. This quote showcases Leonardo’s empirical study of human anatomy, merging his interest in biology and mechanics with the practicalities of human life. This view is emblematic of Leonardo’s drive to understand the purpose behind the structure of the human body, anticipating the principles of modern medicine.

Finally, Leonardo reflects on the relationship between science and practice: “Science is the captain, practice the soldiers.” This metaphor is profound in its simplicity. Science provides the guiding principles, the framework of understanding, while practice executes these principles in the world. Leonardo, through this reflection, suggests that true mastery comes from the harmonious combination of both theory and application—a timeless lesson for modern scientists, engineers, and practitioners alike.

Leonardo’s reflections on science demonstrate not just a keen observational eye but a deep understanding of the principles that govern nature. His statements echo the methods of modern science, where cause and effect, observation, and experimentation reign supreme. His ability to translate abstract ideas into practical knowledge—whether in anatomy, physics, or mathematics—reveals him as a true Renaissance thinker who was constantly ahead of his time. Leonardo’s scientific insights are a testament to the interconnectedness of knowledge—a reminder that science, nature, and humanity are all part of a larger, unified system.

Humanity

-

Whoever would see in what state the soul dwells within the body, let him mark how this body uses its daily habitation. c.a. 76 r. a

-

To the ambitious, whom neither the boon of life, nor the beauty of the world suffice to content, it comes as penance that life is squandered. c.a. 91 v. a

-

The spirit has no voice, for where there is voice there is a body. c.a. 190 v.b

-

Experience, the interpreter between formative nature and the human race, teaches how that nature acts among mortals. 1149.

-

Observe the light and consider its beauty. Blink your eye and look at it. f 49 v.

-

Man has great power of speech, but the greater part thereof is empty and deceitful. f 96 v.

-

Words which fail to satisfy the ear of the listener always either fatigue or weary him. g 47 r.

-

Every evil leaves a sorrow in the memory except the supreme evil, death. h 33 v.

-

Nothing is so much to be feared as a bad reputation. h 40 r.

-

He who does not value life does not deserve it. 1 15 r.

-

What is it that is much desired by men, but which they know not while possessing? It is sleep. 1 56 [8] r.

-

Wine is good, but water is preferable at table. 1 122 [74] v.

-

The knowledge of past times and of the places on the earth is both an ornament and nutriment to the human mind. 1167.

-

Justice requires power, insight, and will; and it resembles the queen-bee. 1191.

-

The memory of benefits is a frail defense against ingratitude. 1194.

Leonardo’s reflections on human nature and behavior reveal a profound understanding of the inner workings of the human soul and its connection to the body. His opening statement—“Whoever would see in what state the soul dwells within the body, let him mark how this body uses its daily habitation”—links the physical state of the body to the state of the soul. For Leonardo, there is no separation between mind and body; the soul is reflected in the way we care for ourselves physically. This idea prefigures the mind-body connection that modern psychology and medicine explore today, where physical health is seen as intertwined with mental well-being.

His reflection on ambition—“To the ambitious, whom neither the boon of life, nor the beauty of the world suffice to content, it comes as penance that life is squandered”—serves as a cautionary tale. Leonardo warns against the insatiability of ambition, pointing out that those who are never satisfied with the gifts of life often end up wasting that very life. This observation speaks to the dangers of materialism and the endless pursuit of more—whether it be wealth, power, or fame—at the cost of appreciating life’s inherent beauty. It resonates deeply in today's fast-paced world, where the constant desire for more often leads to burnout and dissatisfaction.

In a more metaphysical reflection, Leonardo states: “The spirit has no voice, for where there is voice there is a body”. This statement is a beautiful contemplation of the intangible nature of the spirit, which is silent and immaterial. The voice, a physical manifestation, belongs to the body, while the spirit remains beyond physical senses. This duality reminds us of the limits of human perception—we cannot directly access the spirit through sensory experience. Leonardo's insight into the non-material aspect of existence echoes through spiritual and philosophical traditions, inviting us to explore the nature of consciousness and identity.

The role of experience in shaping human understanding comes up again with the observation: “Experience, the interpreter between formative nature and the human race, teaches how that nature acts among mortals”. Here, Leonardo emphasizes that it is through living and observing that we learn the workings of the world. This statement reinforces the idea that wisdom comes not from theory but from lived experience, echoing the sentiments of empiricism that would dominate scientific thought centuries later.

Leonardo’s attention to aesthetic beauty is revealed in his simple yet profound statement: “Observe the light and consider its beauty. Blink your eye and look at it”. This meditation on light—one of Leonardo’s favorite subjects—asks us to pay attention to the transient beauty of the world. Leonardo was known for his deep studies of light and shadow, and here he directs us to observe the fleeting moments that often go unnoticed. It is a call to practice mindfulness, to see the world through fresh eyes and appreciate the small, everyday miracles of light and vision.

In his critique of human speech, Leonardo makes a sharp observation: “Man has great power of speech, but the greater part thereof is empty and deceitful”. This statement, though written centuries ago, feels timelessly relevant in today’s world, where language—in both public discourse and social media—is often used to manipulate or deceive. Leonardo’s warning that much of human speech lacks substance reminds us of the importance of authentic communication and truth in a world filled with noise. This statement, although written centuries ago, is timelessly relevant in our world where language - both in public discourse and on social media - is often used to manipulate or deceive.

Expanding on this, he adds: “Words which fail to satisfy the ear of the listener always either fatigue or weary him”. Leonardo was attuned to the power of words and understood that language, when not wielded effectively, can lose its impact. His advice is timeless: when speaking to others, be mindful of their reactions, for communication is not only about what is said but also how it is received. Leonardo emphasizes the importance of clarity and engagement, principles of communication that are just as relevant in the digital age.

Leonardo’s reflection on death—“Every evil leaves a sorrow in the memory except the supreme evil, death”—is a poignant observation about the finality of death. While all other forms of suffering leave a trace, death wipes away both the memory and the pain. This statement reflects the duality of existence, where death is both an ending and a release from suffering. It offers a philosophical perspective on the impermanence of life, urging us to confront death not as something to fear but as the ultimate equalizer.

“Nothing is so much to be feared as a bad reputation”—turns our attention to social morality. Leonardo understood the power of reputation, which, once tarnished, can be incredibly difficult to repair. In this statement, he warns us to be vigilant about our moral actions and the perception others hold of us. Reputation, for Leonardo, is more lasting than life itself, shaping how we are remembered long after we are gone.

Leonardo’s musings on sleep—“What is it that is much desired by men, but which they know not while possessing? It is sleep.”—demonstrates his ability to find philosophical insights in everyday life. Sleep, a universal human experience, is something we rarely appreciate while we have it, and yet it is craved when absent. This serves as a metaphor for many aspects of human life: we often fail to recognize the value of things until they are lost. Leonardo’s ability to draw deep meaning from simple observations is what makes his reflections so timeless.

He follows this with a simple yet profound word about wine and water: “Wine is good, but water is preferable at the table.” This statement, though humble, reveals Leonardo’s penchant for moderation and simplicity. While he could appreciate the pleasures of life, he also understood the value of restraint and balance—a lesson that resonates with today’s focus on mindful living.

His comment that “the knowledge of past times and of the places on the earth is both an ornament and a nutriment to the human mind” speaks to the importance of history and geography in shaping human understanding. For Leonardo, the past is not merely something to study for its own sake but a source of wisdom that nourishes the mind. He believed in the power of knowledge to elevate the human condition, and his reverence for history underscores the importance of learning from those who came before us.

Finally, Leonardo’s reflections on justice—“Justice requires power, insight, and will; and it resembles the queen-bee”—offers a nuanced view of this central human virtue. For Leonardo, justice is not a passive concept but something that requires strength, wisdom, and determination to enforce. His comparison to the queen-bee suggests that justice is central to the order of society, just as the queen-bee is central to the hive’s survival. This reflection reminds us that justice, like the bee, is delicate yet powerful, requiring constant vigilance to sustain.

Leonardo’s reflections on human nature are both practical and philosophical, offering insights into the moral and ethical dimensions of life. His focus on experience, speech, reputation, and justice provides a blueprint for living with integrity and awareness. These observations, rooted in the Renaissance humanist tradition, continue to resonate today, urging us to engage with the world around us with mindfulness, morality, and wisdom.

Miscellaneous

-

Shun the precepts of those speculators whose arguments are not confirmed by experience. b 4 v.

-

Shun those studies in which the work that results dies with the worker. Forster in. 55 r.

-

Lo some who can call themselves nothing more than a passage for food. Forster in. 74 v.

-

Why does the eye see a thing more clearly in dreams than the imagination when awake? b.m. 278 v.

-

Write of the nature of time as distinct from its geometry. b.m. 176 r.

-

If you kept your body in accordance with virtue your desires would not be of this world. b 3 v.

-

One ought not to desire the impossible. e 31 v.

-

“In general, woman’s desire is opposite to man’s. She wishes the size of the man’s member to be as large as possible, while the man desires the opposite for the woman’s genital parts, so that neither ever attains what is desired…” :-)

Leonardo da Vinci’s Miscellaneous reflections reveal the breadth of his intellectual curiosity, touching on philosophy, human behavior, science, and even humor. In the opening statement, “Shun the precepts of those speculators whose arguments are not confirmed by experience,” Leonardo reaffirms his dedication to empiricism. He warns against speculative thought that isn’t grounded in real-world experience. This reflection feels particularly relevant in a world filled with unverified theories and half-truths, urging us to remain anchored in evidence-based understanding. For Leonardo, experience is not just a guide but a necessity in all endeavors.

He follows this with another critique of certain types of intellectual pursuits: “Shun those studies in which the work that results dies with the worker.” Here, Leonardo is concerned with the legacy of knowledge. He values work that transcends the individual and has lasting impact—be it through art, science, or engineering. This notion speaks directly to his understanding of the transience of life and the importance of contributing something meaningful that will outlast the creator. It’s a timeless reminder that our pursuits should have substance and enduring value, rather than being fleeting passions or pursuits of vanity.

Leonardo's rather sharp observation—“Lo some who can call themselves nothing more than a passage for food”—delivers a biting commentary on those who live without deeper purpose. In this line, he laments with a pinch of humor that some people live only to consume and exist, rather than contribute to society or create something lasting. This sentiment ties into his broader philosophy of purpose and meaning: to live merely for survival is to waste the potential of human life. It’s a call to transcend mere existence and to strive for something greater—be it intellectual, artistic, or spiritual.

Leonardo’s musing—“Why does the eye see a thing more clearly in dreams than the imagination when awake?”—is a fascinating question, one that continues to puzzle philosophers and scientists. Here, Leonardo is commenting on the vividness of dreams, where the mind, unbound by reality, can see and experience things with greater clarity than in waking life. This reflection hints at the power of the subconscious mind—an area that modern psychology continues to explore. Leonardo’s ability to ask such profound questions underscores his deep fascination with the workings of the human mind and perception.

In a more abstract reflection, Leonardo advises: “Write of the nature of time as distinct from its geometry.” This statement touches on the philosophical nature of time, urging a contemplation of time beyond its mathematical measurement. While time can be quantified in seconds, minutes, and hours (geometry), its true essence—how it is experienced and felt—remains elusive. This invites a more existential inquiry into how time shapes our lives and consciousness, beyond the confines of clocks and calendars.

His statement “If you kept your body in accordance with virtue your desires would not be of this world” delves into the intersection of ethics and physical existence. For Leonardo, living a virtuous life is not just a matter of the spirit—it is reflected in the way we care for our physical bodies. He suggests that virtue elevates us above earthly desires, moving us closer to a more spiritual state of being. This echoes Platonic ideals, where the body and soul are intertwined, but the soul’s ultimate goal is to transcend the physical realm.

Leonardo’s pragmatic advice—“One ought not to desire the impossible”—seems simple, yet it speaks to a broader issue of accepting limitations. In a world full of ambition and dreams, Leonardo cautions against setting one’s sights on the unattainable, reminding us to remain grounded. This reflection aligns with his broader focus on practical wisdom and realism, a hallmark of his Renaissance humanism, where knowledge and reason are balanced with measured aspirations.

The humorous reflection on the desires of man and woman... shows Leonardo's willingness to explore all aspects of human desire - even the most intimate. It also suggests a deeper insight into the paradoxes of desire: the idea that humans often long for things that are mutually contradictory or impossible to fully attain. This quote showcases Leonardo’s ability to find wisdom even in the nuances of human relationships.

Leonardo’s reflections are wide-ranging but always rooted in his commitment to truth, observation, and human insight. Whether he’s cautioning against empty intellectual pursuits, musing on the nature of dreams, or commenting on the paradoxes of desire, Leonardo’s mind moves seamlessly between the profound and the practical.

These reflections remind us that wisdom can be found in all corners of life, from the subconscious to the physical world. Leonardo’s ability to engage with these diverse subjects reveals the depth and versatility of his intellect, inspiring us to look for meaning in both the grand and the mundane aspects of human experience.

“While I thought that I was learning how to live,

I have been

learning how to die.”

c.a.

252 r. a

-

Abcd numbers — Jean Paul Richter's "The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci" (1883).

-

b, e, f, g, h — These are likely smaller notebooks or codices, often referred to by the letters of the alphabet. Each collection could have its own numbering system, typically following the folio number and "r." for recto or "v." for verso.

-

'b.m.' stands for the 'Codex of the British Museum.' In this case, '85 v.' refers to folio 85, verso (the back side of the page). Leonardo’s manuscripts often have recto (front side) and verso (back side) pages.

-

c.a. — This stands for Codex Atlanticus, one of the largest and most comprehensive collections of Leonardo's drawings and writings, held at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan. The numbers following the "c.a." (e.g., 252 r. a) refer to specific folios (pages), with "r" meaning recto (front side) and "v" meaning verso (back side).

-

Codex Atlanticus & Codex Arundel — Leonardo's writings and drawings are scattered across many codices, which include famous collections such as the Codex Atlanticus (held in Milan), the Codex Arundel (held in the British Library), and others. Each codex and folio is cataloged based on its current location and how it was divided after Leonardo’s death.

-

Fogli a. 2 r. — "Fogli" means "sheets" in Italian. This likely refers to a particular loose collection of Leonardo’s sheets or notes. "a. 2 r." would indicate sheet (or page) 2, recto.

-

Forster in. 14 r. — This is a reference to the Forster Codices, specifically folio 14 recto in one of the volumes. The Forster Codices are housed at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and include multiple volumes of Leonardo’s notebooks.

-

Leic. 34 r. — This refers to the Codex Leicester, one of Leonardo’s most famous manuscripts, currently owned by Bill Gates. It’s primarily focused on Leonardo’s studies of water, astronomy, and geology. "Leic." stands for Leicester, and "34 r." indicates folio 34 recto.

-

ms. 2038 Bib. Nat. 16 r. — This refers to Manuscript 2038 from the Bibliothèque Nationale (Bib. Nat.) in Paris. The number "16 r." indicates folio 16, recto (front side of the page).

-

Quaderni 1. 7 r. — "Quaderni" refers to notebooks or "exercise books." In this case, it refers to Notebook 1, folio 7 recto. Leonardo often divided his notes across many quaderni.

-

Sul Volo 12 [n J r.] — This is from Codex on the Flight of Birds (Sul Volo degli Uccelli), a treatise by Leonardo on bird flight and aerodynamics. "12" indicates folio 12, and "n J r." suggests some additional notation specific to that manuscript’s cataloging system.

-

Tr. — This likely refers to the Codex Trivulzianus, another manuscript by Leonardo that is mainly focused on language and vocabulary but also contains some scientific notes. The numbers, as with the Codex Atlanticus, refer to specific folio numbers and pages.

Leonardo da Vinci's Weisheit.

“Jeder

Teil strebt danach, sich mit dem GANZEN zu vereinen,

um seiner eigenen Unvollständigkeit zu entkommen.”

„Das, was als Nichts bezeichnet wird, findet sich nur in der Zeit und der Rede. In der Zeit befindet es sich zwischen Vergangenheit und Zukunft und bewahrt nichts von der Gegenwart; in der Rede hingegen, wenn die besprochenen Dinge nicht existieren oder unmöglich sind. In der Natur ist das Nichts nicht zu finden: Es hat seine Gefährten unter den unmöglichen Dingen und existiert aus diesem Grund nicht.

Im Hinblick auf die Zeit liegt das Nichts zwischen Vergangenheit und Zukunft und hat nichts mit der Gegenwart zu tun; seiner Natur nach ist es den unmöglichen Dingen zuzuordnen: Daher, wie bereits erwähnt, hat es keine Existenz, denn wo nichts ist, müsste es zwangsläufig ein Vakuum geben. cf. No. 916.

Unter den großen Dingen, die wir um uns finden, ist das Vorhandensein des NICHTS das größte. Es wohnt in der Zeit, streckt seine Glieder in die Vergangenheit und Zukunft und nimmt damit alle Werke der Vergangenheit und der Zukunft in sich auf, sowohl der Natur als auch der Lebewesen, und besitzt nichts vom unteilbaren Jetzt. Es erstreckt sich jedoch nicht auf das Wesen irgendeiner Sache. c.a. 398 v. d.

Mitten in der Unermesslichkeit der Dinge um uns herum nimmt das Vorhandensein des Nichts den ersten Platz ein, und seine Funktion erstreckt sich auf die Dinge, die keine Existenz haben, und sein Wesen liegt in Bezug auf die Zeit zwischen Vergangenheit und Zukunft und besitzt nichts von der Gegenwart.

Dieses NICHTS ist in Teil und Ganzem gleich, dem Teilbaren und dem Unteilbaren, und seine Kraft erstreckt sich nicht auf die Dinge der Natur, denn da die Natur ein Vakuum verabscheut, verliert dieses Nichts sein Wesen, weil das Ende eines Dings der Anfang eines anderen ist. Es macht keinen Unterschied, ob wir es teilen, multiplizieren, addieren oder subtrahieren, wie es die Mathematiker in ihrem zehnten Zeichen, das dieses NICHTS [Null] darstellt, zeigen. Und seine Kraft erstreckt sich nicht auf die Dinge der Natur. b.m. 131 r.

Das Nichts hat eine gemeinsame Oberfläche mit einem Ding, und das Ding hat eine gemeinsame Oberfläche mit dem Nichts, und die Oberfläche eines Dings ist kein Teil dieses Dings. Es folgt, dass die Oberfläche des Nichts kein Teil dieses Nichts ist; es muss daher eine bloße Oberfläche sein, die die gemeinsame Grenze zweier Dinge bildet, die in Berührung sind; so bildet die Wasseroberfläche keinen Teil des Wassers und folglich auch keinen Teil der Atmosphäre, noch sind andere Körper zwischen ihnen vorhanden. Was trennt also die Atmosphäre vom Wasser? Es ist notwendig, dass es eine gemeinsame Grenze gibt, die weder Luft noch Wasser ist, aber ohne Substanz, denn ein Körper, der zwischen zwei Körpern liegt, verhindert ihren Kontakt, und dies geschieht im Wasser mit der Luft nicht, da sie ohne Zwischenschicht in Kontakt stehen.

Daher sind sie verbunden, und man kann die Luft nicht heben oder bewegen, ohne das Wasser mit zu bewegen, noch kann man das flache Ding vom anderen heben, ohne es durch die Luft zurückzuziehen. Daher ist eine Oberfläche die gemeinsame Grenze zweier Körper, die nicht kontinuierlich sind, und gehört nicht zu dem einen oder dem anderen, denn wenn die Oberfläche Teil davon wäre, hätte sie ein teilbares Volumen, während sie jedoch nicht teilbar ist, und das Nichts diese Körper voneinander trennt. b.m. 159 v."

Leonardo da Vincis Reflexionen über das Nichts offenbaren ein tiefes Verständnis der abstrakten und paradoxen Natur von Zeit, Raum und Existenz. Er beschreibt das Nichts nicht nur als Abwesenheit von Dingen, sondern als integralen Bestandteil unserer Wahrnehmung der Realität. Interessanterweise verortet Leonardo das Nichts in der Zeit und in der Sprache und betont, dass es den Raum zwischen Vergangenheit und Zukunft einnimmt, jedoch niemals die Gegenwart berührt. Dies ist eine kraftvolle Metapher für das menschliche Bewusstsein und die Existenz – das Nichts ist der Ort, an dem wir uns ständig befinden, immer zwischen dem, was war, und dem, was kommt, aber niemals ganz die flüchtige Gegenwart erfassend.

In seinen Diskussionen über die Natur macht Leonardo deutlich, dass das Nichts keinen Platz in der physischen Welt hat. Für ihn verabscheut die Natur ein Vakuum, und das Vorhandensein des Nichts ist nur konzeptionell – es gehört in den Bereich der Unmöglichkeiten. Dies erinnert an antike philosophische Debatten über die Existenz eines Vakuums, insbesondere jene der griechischen Philosophen wie Parmenides und Aristoteles, die gegen die Vorstellung eines Vakuums in der Natur argumentierten. Leonardos Ansatz ist jedoch eher mathematisch, da er das Nichts mit dem Konzept der Null verknüpft, was auf seine funktionale Rolle im menschlichen Wissen hinweist, aber gleichzeitig seine Nichtexistenz in der physischen Welt betont.

Leonardos Idee, dass das Nichts bis ins Unendliche teilbar ist, aber keine Substanz hat, ist auch eine brillante Reflexion über Mathematik und Metaphysik. Die von ihm beschriebene Grenze zwischen Wasser und Luft – eine Oberfläche, die weder Teil des Wassers noch der Luft ist – weist auf eine tiefere Meditation über die Grenzen der Wahrnehmung hin. Sie deutet darauf hin, dass die Grenze zwischen etwas und nichts, ähnlich wie der Rand einer Idee, zart und schwer fassbar ist, aber von entscheidender Bedeutung. Diese Grenze fordert die Natur der Realität und Wahrnehmung heraus und erinnert an moderne Erkundungen der Quantenphysik, wo Teilchen scheinbar gleichzeitig existieren und nicht existieren können.

Schließlich zeigt seine Aussage, dass „das Nichts eine gemeinsame Oberfläche mit einem Ding hat“, Leonardos philosophische Tiefe. Er scheint anzudeuten, dass Existenz und Nichtexistenz zwei Seiten derselben Medaille sind. Die Art und Weise, wie er die Interaktion zwischen Körpern und den Räumen, die sie einnehmen, untersucht, spricht eine zeitlose Frage über die Natur des Seins an – eine Frage, die Philosophen und Wissenschaftler bis heute diskutieren.

Leonardos Kontemplationen über das Nichts bieten uns einen Einblick in seine doppelte Identität als Wissenschaftler und Philosoph. Seine Fähigkeit, die Grenzen der empirischen Beobachtung und der metaphysischen Spekulation zu überschreiten, macht diese Reflexionen besonders reich. Hier ist das Nichts nicht nur eine Abwesenheit, sondern ein wesentlicher Bestandteil des Gewebes der Realität, der sowohl die natürliche Welt als auch den menschlichen Geist leitet. Dies positioniert Leonardo nicht nur als Künstler und Erfinder, sondern als Denker, der sich tief mit einigen der schwierigsten und abstraktesten Fragen der Existenz auseinandersetzte.

Leonardo's WEISHEIT

Philosophie

-

Es ist möglich, sich alles, was Substanz hat, als in eine unendliche Anzahl von Teilen teilbar vorzustellen.

-

Die Natur ist voller unendlicher Ursachen, die noch nie in der Erfahrung aufgetreten sind!

-

Das höchste Glück wird die größte Ursache des Elends sein, und die Vollkommenheit der Weisheit die Gelegenheit zur Torheit. c.a. 39 v. c

-

Das Alter gleitet heimlich und täuscht den einen und den anderen; nichts ist vergänglicher als die Jahre, doch wer Tugend sät, erntet Ehre. c.a. 71 v. a

-

Der sexuelle Antrieb zur Fortpflanzung wird in Kreativität umgewandelt. -D

-

Ein gut gelebtes Leben ist lang.

-

So wie ein gut verbrachter Tag glücklichen Schlaf bringt, so bringt ein gut genutztes Leben einen glücklichen Tod. Tr. 28 a

-

Das Nichts hat kein Zentrum, und seine Grenzen sind das Nichts. Mein Gegner sagt, dass das Nichts und das Vakuum ein und dasselbe sind. c.a. 289 v. b

-

Intellektuelle Leidenschaft vertreibt Sinnlichkeit. c.a. 358 v. a

-

Die Seele kann niemals durch die Verderbtheit des Körpers infiziert werden, sondern wirkt im Körper wie der Wind, der den Klang der Orgel erzeugt. Tr. 71 a

-

O Mathematiker, bringt Licht in diesen Irrtum.

-

Die Gedanken wenden sich der Hoffnung zu. 1 c.a. 68 v. b

-

Rüge deinen Freund im Geheimen und lobe ihn offen. 1194.

-

Oh! Spekulanten des Perpetuum Mobile, wie viele vergebliche Projekte habt ihr geschaffen! 1206.

-

Es ist leichter, am Anfang zu widerstehen als am Ende.

-

Denn nichts kann geliebt oder gehasst werden, wenn es nicht zuerst bekannt ist.

-

Weisheit ist die Tochter der Erfahrung. 1150.

-

Die Wahrheit allein war die Tochter der Zeit. m 58 v.

-

Kleine Räume oder Wohnungen lenken den Geist auf den rechten Weg; große führen ihn in die Irre. ms. 2038 Bib. Nat. 16 r.

-

Nenne nicht das Reichtum, was verloren gehen kann; Tugend ist unser wahrer Reichtum. ms. 2038 Bib. Nat. 34 v.

-

Jede Handlung, die von der Natur ausgeführt wird, erfolgt auf dem kürzesten Weg. b.m. 85 v.

-

Wo der Abstieg leichter ist, da ist der Aufstieg schwieriger. b.m. 120 r.

Leonardos philosophische Reflexionen zeigen einen Geist, der nicht nur die Mechanik der physischen Welt, sondern auch das Wesen der menschlichen Existenz verstehen wollte. Er beginnt mit einer Aussage, die die unendliche Teilbarkeit der Materie berührt, und legt nahe, dass alles, was Substanz hat, unendlich teilbar ist. Diese Idee spiegelt die atomistischen Theorien von Demokrit wider und weist auf spätere Entwicklungen in der Quantenphysik hin, in der Teilchen als auf einem Wahrscheinlichkeitskontinuum existierend verstanden werden, anstatt als feste, unteilbare Objekte. Leonardos Brillanz liegt in seiner Fähigkeit, abstraktes wissenschaftliches Denken mit metaphysischen Fragen zu verbinden und die Grenzen des menschlichen Verständnisses auszuloten.

Seine Behauptung, dass „die Natur voller unendlicher Ursachen ist, die noch nie in der Erfahrung aufgetreten sind“, ist sowohl demütig als auch revolutionär. Sie erkennt an, dass es Phänomene und Kräfte gibt, die über das hinausgehen, was wir wahrnehmen oder messen können. Dies spiegelt sich in der modernen wissenschaftlichen Forschung wider, die weiterhin Schichten von Komplexität in der Natur aufdeckt, die unsere früheren Annahmen herausfordern. Leonardo erinnert uns daran, dass das Universum weit größer ist, als das menschliche Verständnis derzeit erfassen kann.

Die Beobachtung, dass das höchste Glück zum Elend und die Vollkommenheit der Weisheit zur Torheit führt, zeigt Leonardos tiefes Verständnis für die menschliche Natur. Dieses Paradoxon taucht in der stoischen und östlichen Philosophie immer wieder auf: die Vorstellung, dass Extreme – sei es in Freude oder Weisheit – zu ihrem Gegenteil führen können. Leonardo sieht die Suche nach absoluten Idealen als gefährlich an und warnt vor dem notwendigen Gleichgewicht im Leben. Wer nach dem höchsten Glück oder der höchsten Weisheit strebt, riskiert, enttäuscht oder von der Realität losgelöst zu werden.

Er setzt dieses Thema fort, indem er über die Vergänglichkeit der Zeit nachdenkt: „Das Alter gleitet heimlich und täuscht den einen und den anderen; nichts ist vergänglicher als die Jahre, doch wer Tugend sät, erntet Ehre.“ Leonardo spricht von der Vergänglichkeit des Lebens und dem subtilen Voranschreiten der Zeit, das uns oft überrascht. Sein Glaube an die Beständigkeit der Tugend spiegelt die humanistische Tradition wider und betont, dass wir, auch wenn wir die Zeit nicht aufhalten können, mit Integrität und Ehre handeln können, um etwas Bleibendes zu hinterlassen. Tugend ist in diesem Fall das Gegenmittel zur Vergänglichkeit des Daseins.

Leonardos Kommentar zur Umwandlung des sexuellen Antriebs in Kreativität ist eine tiefe psychologische Einsicht. Er erkennt die Umwandlung primitiver Triebe in höhere Formen des Ausdrucks an – ein Prozess, der Jahrhunderte später in Freuds Theorie der Sublimierung eine Parallele findet. Hier sieht Leonardo die Möglichkeit, biologische Bedürfnisse in etwas Intellektuelles und Künstlerisches zu verwandeln, was seinen Glauben an das erhebende Potenzial der menschlichen Natur zeigt.

Die philosophische Reflexion „Ein gut gelebtes Leben ist lang“ und „so wie ein gut verbrachter Tag glücklichen Schlaf bringt, so bringt ein gut genutztes Leben einen glücklichen Tod“ fasst Leonardos Ansichten über Sterblichkeit und Lebenszweck zusammen. Für ihn wird die Qualität des Lebens nicht an seiner Länge gemessen, sondern daran, wie es gelebt wird. Dies erinnert an die Lehren des Stoizismus und Daoism, wo ein Leben voller sinnvollen Handelns, statt von hedonistischen Vergnügungen, am Ende Frieden bringt. Die Metapher des Schlafes als Symbol für den Tod ist besonders ergreifend und deutet darauf hin, dass der Tod nicht gefürchtet werden muss, wenn man voll und ganz gelebt hat.

In Leonardos Erforschung des Nichts kehrt er zu seiner Faszination für das Vakuum und das Unmögliche zurück. Seine Vorstellung, dass „das Nichts kein Zentrum hat und seine Grenzen das Nichts sind“, spricht für sein Verständnis der Begrenzungen des menschlichen Wissens. Das Nichts als Konzept verschiebt die Grenzen des Denkens, lässt die sicheren Schranken der physischen Realität hinter sich und betritt den Bereich der abstrakten Spekulation. Es ist ein wiederkehrendes Thema in seinem Werk – eine Reflexion über seine unermüdliche Neugier auf die unsichtbaren Kräfte, die unser Universum formen.

Intellektuelle Leidenschaft, die Sinnlichkeit vertreibt, ist eine weitere psychologische Einsicht Leonardos. Für ihn übersteigt das Streben nach Wissen und Weisheit die physischen Begierden. Diese Ansicht knüpft an seinen breiteren Glauben an das menschliche Potenzial an: Durch die Konzentration auf intellektuelle Entwicklung können wir uns über die instinktiven Triebe erheben, die unser Leben oft dominieren. Dies bekräftigt die Vorstellung, dass der Verstand, nicht der Körper, der Sitz wahrer Macht und Tugend ist.

Leonardos Reflexionen über Freundschaft und Lob – einen Freund im Geheimen zu rügen und ihn offen zu loben – spiegeln uralte Prinzipien von Ehre und Vertrauen wider. Jemanden öffentlich zu kritisieren ist ein Verrat, während ihn öffentlich zu ehren eine Form der Großzügigkeit und Anerkennung ist. Diese einfache, aber tiefe Weisheit hat auch heute noch Gültigkeit, in einer Welt, in der öffentliche Kritik dominiert und private Tugenden unerkannt bleiben.

Dann wendet Leonardo seinen scharfen Verstand dem Perpetuum Mobile und denjenigen zu, die darüber spekulieren, und bezeichnet sie als Schöpfer vergeblicher Projekte. Hier zeigt sich Leonardos Skepsis gegenüber grandiosen, unmöglichen Bestrebungen – seine Philosophie ist in den Grenzen des menschlichen Wissens und der Fähigkeiten verankert. Er warnt uns, in Wissenschaft und Leben vorsichtig mit falschen Versprechungen zu sein.

In seinen Überlegungen zur Wahrheit stellt Leonardo fest, dass Weisheit die Tochter der Erfahrung ist – eine Vorstellung, die Wissen mit praktischer, gelebter Realität verbindet. Seine Aussage, dass „die Wahrheit allein die Tochter der Zeit war“, erhebt die Wahrheit auf eine höhere Ebene und deutet darauf hin, dass sich die Wahrheit allmählich durch die Zeit offenbart, so wie die Erfahrung zur Weisheit führt. Dies bietet eine elegante Versöhnung zwischen intellektueller Entdeckung und dem Verstreichen der Zeit.

Schließlich sind Leonardos Überlegungen zu Tugend und Reichtum zeitlos. „Nenne nicht das Reichtum, was verloren gehen kann; Tugend ist unser wahrer Reichtum.“ In einer Welt, die von materiellem Reichtum besessen ist, erinnert uns Leonardo daran, dass nur die Tugend dauerhaft ist und nicht genommen werden kann. Es ist ein ernüchternder Gedanke, der auch in der heutigen konsumorientierten Gesellschaft relevant bleibt. Indem er uns auffordert, Tugend zu kultivieren, anstatt Besitz anzuhäufen, tritt Leonardo für ein sinnvolles Leben anstelle von Materialismus ein.

Am Ende bilden Leonardos philosophische Reflexionen ein kohärentes Weltbild, das sowohl auf humanistischen Prinzipien als auch auf einer scharfsinnigen Beobachtung der Natur basiert. Seine Gedanken übersteigen die Zeit und bieten uns Weisheit, die heute genauso anwendbar ist wie zur Zeit der Renaissance. Das Zusammenspiel von Zeit, Sterblichkeit, menschlicher Tugend und den Grenzen des Wissens schafft ein reiches Ideenmuster, das diejenigen, die sich darauf einlassen, weiterhin inspiriert und herausfordert.

Wissenschaft

-

Jede Größe ist intellektuell als unendlich teilbar vorstellbar. 1216.

-

Die Erfahrung, der Dolmetscher zwischen der einfallsreichen Natur und der menschlichen Spezies, lehrt, dass das, was die Natur ausarbeitet, nicht anders funktionieren kann als durch Vernunft. c.a. 86 r. a

-

Es gibt in der Natur kein Ergebnis ohne Ursache; verstehe die Ursache und du wirst das Experiment nicht benötigen. c.a. 147 v. a

-

Die Erfahrung ist niemals im Unrecht; nur dein Urteil irrt sich. c.a. 154 r. h

-

Zu Unrecht klagen die Menschen gegen die Erfahrung und beschuldigen sie mit bitteren Vorwürfen des Betrugs. c.a. 154 r. c

-

Es kann keinen Klang geben, wo keine Bewegung oder Erschütterung der Luft ist. b 4 v.

-

Wissenschaft ist das Wissen um die Dinge, die möglich sind, in der Gegenwart und Vergangenheit; Vorwissen ist das Wissen um die Dinge, die geschehen können. Tr. 46 r.

-

Jede Handlung der Natur erfolgt auf dem kürzesten möglichen Weg. Quaderni iv 16 r.

-

Die Erde wird durch das Gewicht eines winzigen Vogels, der auf ihr ruht, aus ihrer Position bewegt. b.m. 19 r.

-

In Flüssen ist das Wasser, das du berührst, das Letzte dessen, was vergangen ist, und das Erste dessen, was kommt: So verhält es sich mit der Gegenwart der Zeit. Tr. 63 a

-

Viele Male wird ein und dasselbe Ding von zwei Gewalten gezogen, nämlich der Notwendigkeit und der Kraft. Tr. 70 a

-

Jede kontinuierliche Größe ist unendlich teilbar; daher wird die Teilung dieser Größe niemals zu einem Punkt führen. b.m. 204 v.

-

Bewegung ist die Ursache allen Lebens. h 141 [2 v.] r.

-

Die Wissenschaft ist der Kapitän, die Praxis die Soldaten. 1160.

-

Der Mann, der die höchste Gewissheit der Mathematik infrage stellt, nährt sich von Verwirrung. 1157.

-

Es gibt keine Gewissheit in den Wissenschaften, wenn nicht eine der mathematischen Wissenschaften angewendet werden kann. 1158.

-

Ein Punkt ist kein Teil einer Linie. Tr. 63 a

-

Die Ursache, die die Natur hervorbringt, erzeugt den Effekt auf die kürzest mögliche Weise. b.m. 174 v.

-

Der Ursprung des Penis liegt auf dem Schambein. Er wird so gestützt, um den beim Geschlechtsverkehr wirkenden Kräften zu widerstehen. Wenn dieses Knochenstück nicht existieren würde, würden diese Kräfte den Penis beim Aufeinandertreffen mit Widerstand zurückdrängen, und er würde oft mehr in den Körper des Ausführenden als in den des Empfängers eindringen...

Leonardo da Vincis Reflexionen über die Wissenschaft zeigen einen Geist, der nicht nur seiner Zeit weit voraus war, sondern auch tief in den Prinzipien der Beobachtung, Logik und Natur verwurzelt war. Sein Ansatz zur Wissenschaft ist ganzheitlich und verbindet Mathematik, Physik und Biologie. Dies zeigt sich in seiner Eröffnungsaussage: „Jede Größe ist intellektuell als unendlich teilbar vorstellbar.“ Dies knüpft an das Konzept der Unendlichkeit an – ein Thema, das er häufig erkundete. Lange bevor die moderne Mathematik die Idee formalisierte, verstand Leonardo intuitiv, dass Materie und Raum endlos teilbar sind, ein Konzept, das heute sowohl in der Infinitesimalrechnung als auch in der Quantenmechanik zentral ist. In dieser Hinsicht antizipiert Leonardo die Zukunft der wissenschaftlichen Erforschung, bei der je tiefer wir vordringen, desto mehr Schichten wir entdecken.

Seine Behauptung, dass „die Erfahrung der Dolmetscher zwischen der einfallsreichen Natur und der menschlichen Spezies ist“, zeigt Leonardos Respekt vor dem empirischen Wissen. Er sah die Erfahrung als Brücke zwischen der Komplexität der Natur und der menschlichen Fähigkeit, sie zu verstehen. Diese Lernmethode durch Beobachtung und Experiment bildet das Fundament der modernen wissenschaftlichen Methodik. Er erkannte an, dass die Natur nach Vernunft funktioniert, was bedeutet, dass hinter jedem natürlichen Ereignis eine logische Erklärung steckt, auch wenn diese noch nicht entdeckt wurde.

In seiner Reflexion „Es gibt in der Natur kein Ergebnis ohne Ursache“ trifft Leonardo den Kern des wissenschaftlichen Prinzips der Kausalität. Für ihn ist das Verständnis der Ursache entscheidend – sobald die Ursache bekannt ist, erübrigen sich spekulative Experimente. Dies spiegelt den modernen wissenschaftlichen Fokus auf die Suche nach fundamentalen Gesetzen zur Erklärung des Universums wider, wie man sie in Bereichen wie der Physik und Chemie findet. Leonardos Glaube an eine Ursache-Wirkung-Struktur in der Natur unterstreicht sein Streben nach einer Welt, die durch Vernunft und nicht durch Aberglauben oder Vermutungen verstanden wird.

Leonardo verteidigt die Zuverlässigkeit der empirischen Beobachtung, indem er diejenigen tadelt, die der Erfahrung die Schuld für ihre Missverständnisse geben: „Die Erfahrung ist niemals im Unrecht; nur dein Urteil irrt sich.“ Hier verteidigt er die Zuverlässigkeit der empirischen Beobachtung und legt nahe, dass der menschliche Fehler in der Fehlinterpretation und nicht in der Beobachtung selbst liegt. Dieser Gedanke kommt den modernen Wissenschaftlern entgegen, die ihre Hypothesen und Modelle angesichts neuer Erkenntnisse ständig verfeinern.

Seine Gedanken zu Klang und Bewegung sind ebenso beeindruckend: „Es kann keinen Klang geben, wo keine Bewegung oder Erschütterung der Luft ist.“ Diese einfache, aber tiefgründige Aussage destilliert das Wesen der Akustik – eine Wissenschaft, die zu Leonardos Zeit noch in den Kinderschuhen steckte. Indem er den Klang mit der Bewegung der Luft verbindet, hebt Leonardo die physikalischen Eigenschaften des Klangs hervor und antizipiert das, was später in der Wellentheorie weiter erforscht wurde.

Leonardos Fokus auf die Ökonomie der Natur – „jede Handlung der Natur erfolgt auf dem kürzesten möglichen Weg“ – zeigt sein Verständnis für die Effizienz in der natürlichen Welt. Für Leonardo arbeitet die Natur mit minimalem Aufwand, ein Prinzip, das in der modernen Physik, insbesondere in der Thermodynamik und den Bewegungsgesetzen, zentral ist. Die Idee der Effizienz in den Prozessen der Natur spiegelt das heutige Verständnis wider, dass das Universum, gesteuert durch physikalische Gesetze, zu Zuständen minimaler Energie tendiert.

In einer seiner zartesten Beobachtungen stellt Leonardo fest: „Die Erde wird durch das Gewicht eines winzigen Vogels, der auf ihr ruht, aus ihrer Position bewegt.“ Hier fasst er die Verbundenheit aller Dinge zusammen, von den kleinsten Kreaturen bis zu den größten Himmelskörpern. Obwohl das Gewicht eines Vogels vernachlässigbar erscheinen mag, spiegelt Leonardos Aussage sein Verständnis von Physik und Kräften wider, bei denen auch kleine Handlungen Konsequenzen haben. Dies steht im Einklang mit dem modernen Gravitationsprinzip, nach dem jedes Objekt eine Kraft auf jedes andere Objekt ausübt, egal wie klein.

Die metaphorische Reflexion über Zeit und Flüsse – „Das Wasser, das du berührst, ist das Letzte dessen, was vergangen ist, und das Erste dessen, was kommt: So verhält es sich mit der Gegenwart der Zeit“ – ist nicht nur poetisch, sondern fasst auch Leonardos Verständnis von der Kontinuität der Zeit zusammen. So wie Heraklit einst bemerkte, dass man nicht zweimal in denselben Fluss steigen kann, reflektiert Leonardo die flüchtige Natur des gegenwärtigen Moments und sieht die Zeit als sowohl fließend als auch ewig. Diese Fluidität der Zeit bleibt ein faszinierendes Konzept für die moderne Physik, insbesondere in den Bereichen der Relativität und Zeitdilatation.

In seinen Beobachtungen zur Bewegung erkundet Leonardo die Kräfte der Notwendigkeit und der Kraft – natürliche Kräfte, die Materie bewegen. Seine Einsichten zur Teilung von Größen und ihrer unendlichen Teilbarkeit unterstreichen weiter seine Faszination für mathematische Prinzipien. Er begreift, dass Naturphänomene bis zu ihren kleinsten Teilen unendlich teilbar sind – ein revolutionäres Konzept, das in den modernen Theorien über Raum und Materie mitschwingt.

Leonardos Gedanken über den menschlichen Körper sind ebenso tiefgründig. Sein detailliertes Verständnis der Anatomie zeigt sich in Aussagen wie „Der Ursprung des Gliedes liegt auf dem Schambein“, eine Reflexion über Biomechanik und Funktionalität in der menschlichen Fortpflanzung. Dieser Satz zeigt Leonardos empirische Studien der menschlichen Anatomie und seine Verbindung von Biologie und Mechanik mit den praktischen Aspekten des menschlichen Lebens. Diese Ansicht ist ein Sinnbild für Leonardos Bestreben, den Zweck hinter der Struktur des menschlichen Körpers zu verstehen und damit die Prinzipien der modernen Medizin vorwegzunehmen.

Schließlich reflektiert Leonardo über das Verhältnis von Wissenschaft und Praxis: „Die Wissenschaft ist der Kapitän, die Praxis die Soldaten.“ Diese Metapher ist in ihrer Einfachheit tiefgründig. Die Wissenschaft liefert die Leitprinzipien, das Rahmenwerk des Verstehens, während die Praxis diese Prinzipien in der Welt ausführt. Leonardo deutet mit dieser Reflexion an, dass wahre Meisterschaft aus der harmonischen Kombination von Theorie und Anwendung entsteht – eine zeitlose Lektion für moderne Wissenschaftler, Ingenieure und Praktiker gleichermaßen.

Leonardos Reflexionen über die Wissenschaft zeigen nicht nur ein scharfes Beobachtungsvermögen, sondern auch ein tiefes Verständnis der Prinzipien, die die Natur beherrschen. Seine Aussagen spiegeln die Methoden der modernen Wissenschaft wider, in der Ursache und Wirkung, Beobachtung und Experiment an erster Stelle stehen. Seine Fähigkeit, abstrakte Ideen in praktisches Wissen zu übersetzen – sei es in der Anatomie, Physik oder Mathematik – offenbart ihn als einen wahren Renaissance-Denker, der seiner Zeit stets voraus war. Leonardos wissenschaftliche Einsichten sind ein Zeugnis für die Verbundenheit des Wissens – eine Erinnerung daran, dass Wissenschaft, Natur und Menschlichkeit alle Teil eines größeren, einheitlichen Systems sind.

Humanität

-

Wer sehen möchte, in welchem Zustand die Seele im Körper wohnt, der soll darauf achten, wie dieser Körper seinen täglichen Wohnsitz nutzt. c.a. 76 r. a

-

Für den Ehrgeizigen, den weder das Geschenk des Lebens noch die Schönheit der Welt zufriedenstellen, ist es eine Buße, dass das Leben verschwendet wird. c.a. 91 v. a

-

Der Geist hat keine Stimme, denn wo eine Stimme ist, da ist ein Körper. c.a. 190 v.b

-

Die Erfahrung, der Dolmetscher zwischen der gestaltenden Natur und dem Menschengeschlecht, lehrt, wie diese Natur unter Sterblichen wirkt. 1149.

-

Beobachte das Licht und betrachte seine Schönheit. Blinzele und sieh es dir an. f 49 v.

-

Der Mensch hat eine große Sprachkraft, doch der größte Teil davon ist leer und trügerisch. f 96 v.

-

Worte, die das Ohr des Zuhörers nicht zufriedenstellen, ermüden oder langweilen ihn immer. g 47 r.

-

Jedes Übel hinterlässt eine Trauer im Gedächtnis, außer dem höchsten Übel, dem Tod. h 33 v.

-

Nichts ist so sehr zu fürchten wie ein schlechter Ruf. h 40 r.

-

Wer das Leben nicht wertschätzt, verdient es nicht. 1 15 r.

-

Was ist es, das die Menschen sehr begehren, es aber nicht kennen, während sie es besitzen? Es ist der Schlaf. 1 56 [8] r.

-

Wein ist gut, aber Wasser ist am Tisch vorzuziehen. 1 122 [74] v.

-

Das Wissen über vergangene Zeiten und die Orte der Erde ist sowohl ein Schmuckstück als auch eine Nahrung für den menschlichen Geist. 1167.

-

Gerechtigkeit erfordert Macht, Einsicht und Willen; und sie gleicht der Königin der Bienen. 1191.

-

Das Gedächtnis an Wohltaten ist ein schwacher Schutz gegen Undankbarkeit. 1194.

Leonardo da Vincis Reflexionen über die menschliche Natur und das Verhalten zeigen ein tiefes Verständnis für die inneren Mechanismen der menschlichen Seele und ihre Verbindung zum Körper. Seine Eröffnungsaussage – „Wer sehen möchte, in welchem Zustand die Seele im Körper wohnt, der soll darauf achten, wie dieser Körper seinen täglichen Wohnsitz nutzt“ – verbindet den physischen Zustand des Körpers mit dem Zustand der Seele. Für Leonardo gibt es keine Trennung zwischen Geist und Körper; die Seele spiegelt sich in der Art und Weise wider, wie wir uns körperlich um uns selbst kümmern. Diese Idee ist eine Vorwegnahme der Verbindung zwischen Geist und Körper, welche die moderne Psychologie und Medizin heute erforscht, in denen körperliche Gesundheit als eng mit dem geistigen Wohlbefinden verbunden angesehen wird.

Seine Reflexion über den Ehrgeiz – „Für den Ehrgeizigen, den weder das Geschenk des Lebens noch die Schönheit der Welt zufriedenstellen, ist es eine Buße, dass das Leben verschwendet wird“ – dient als warnendes Beispiel. Leonardo warnt vor dem unersättlichen Ehrgeiz und weist darauf hin, dass diejenigen, die niemals mit den Gaben des Lebens zufrieden sind, oft genau dieses Leben verschwenden. Diese Beobachtung spricht die Gefahren des Materialismus und der endlosen Jagd nach mehr an – sei es Reichtum, Macht oder Ruhm – auf Kosten der Wertschätzung der innewohnenden Schönheit des Lebens. Diese Reflexion ist auch heute noch aktuell in unserer schnelllebigen Welt, in der das ständige Verlangen nach mehr oft zu Burnout und Unzufriedenheit führt.

In einer metaphysischen Reflexion stellt Leonardo fest: „Der Geist hat keine Stimme, denn wo eine Stimme ist, da ist ein Körper.“ Diese Aussage ist eine wunderschöne Betrachtung der immateriellen Natur des Geistes, der stumm und immateriell ist. Die Stimme, eine physische Manifestation, gehört dem Körper, während der Geist jenseits der physischen Sinne bleibt. Diese Dualität erinnert uns an die Grenzen der menschlichen Wahrnehmung – wir können den Geist nicht direkt durch sensorische Erfahrung erfassen. Leonardos Einsicht in den immateriellen Aspekt der Existenz spiegelt sich in spirituellen und philosophischen Traditionen wider und lädt uns ein, die Natur des Bewusstseins und der Identität zu erforschen.

Die Rolle der Erfahrung bei der Formung des menschlichen Verständnisses kommt erneut in der Beobachtung „Die Erfahrung, der Dolmetscher zwischen der gestaltenden Natur und dem Menschengeschlecht, lehrt, wie diese Natur unter Sterblichen wirkt“ zum Ausdruck. Hier betont Leonardo, dass wir durch das Leben und das Beobachten die Funktionsweise der Welt erlernen. Diese Aussage verstärkt die Idee, dass Weisheit nicht aus der Theorie, sondern aus gelebter Erfahrung stammt, was dem Empirismus entspricht, der Jahrhunderte später das wissenschaftliche Denken dominierte.

Leonardos Aufmerksamkeit für ästhetische Schönheit wird in seiner einfachen, aber tiefgründigen Aussage „Beobachte das Licht und betrachte seine Schönheit. Blinzele und sieh es dir an“ deutlich. Diese Meditation über das Licht – eines von Leonardos Lieblingsthemen – fordert uns auf, die vergängliche Schönheit der Welt zu beachten. Leonardo war bekannt für seine tiefen Studien von Licht und Schatten, und hier fordert er uns auf, die flüchtigen Momente zu beobachten, die oft unbemerkt bleiben. Es ist ein Aufruf zur Achtsamkeit, die Welt mit neuen Augen zu sehen und die kleinen, alltäglichen Wunder des Lichts und der Vision zu schätzen.

In seiner Kritik an der menschlichen Rede macht Leonardo eine scharfe Beobachtung: „Der Mensch hat eine große Sprachkraft, doch der größte Teil davon ist leer und trügerisch.“ Diese Feststellung wurde zwar vor Jahrhunderten geschrieben, ist aber in unserer Welt, in der die Sprache - sowohl im öffentlichen Diskurs als auch in den sozialen Medien - häufig zur Manipulation oder Täuschung verwendet wird, zeitlos relevant. Leonardos Warnung, dass ein Großteil der menschlichen Rede an Substanz mangelt, erinnert uns an die Bedeutung authentischer Kommunikation und Wahrheit in einer Welt voller Lärm.

Er erweitert diesen Gedanken und fügt hinzu: „Worte, die das Ohr des Zuhörers nicht zufriedenstellen, ermüden oder langweilen ihn stets.“ Leonardo war sich der Macht der Worte bewusst und verstand, dass Sprache, wenn sie nicht effektiv eingesetzt wird, ihre Wirkung verlieren kann. Sein Rat ist zeitlos: Beim Sprechen mit anderen sollte man auf ihre Reaktionen achten, denn Kommunikation besteht nicht nur darin, was gesagt wird, sondern auch darin, wie es aufgenommen wird. Leonardo betont die Bedeutung von Klarheit und Engagement – Prinzipien der Kommunikation, die auch im digitalen Zeitalter von großer Relevanz sind."

Leonardos Reflexion über den Tod – „Jedes Übel hinterlässt eine Trauer im Gedächtnis, außer dem höchsten Übel, dem Tod“ – ist eine ergreifende Beobachtung über die Endgültigkeit des Todes. Während alle anderen Formen des Leidens eine Spur hinterlassen, löscht der Tod sowohl die Erinnerung als auch den Schmerz aus. Diese Aussage reflektiert die Dualität des Daseins, in der der Tod sowohl ein Ende als auch eine Befreiung vom Leiden darstellt. Sie bietet eine philosophische Perspektive auf die Vergänglichkeit des Lebens und fordert uns auf, den Tod nicht als etwas zu fürchten, sondern als den ultimativen Ausgleich.

Seine nächste Reflexion – „Nichts ist so sehr zu fürchten wie ein schlechter Ruf“ – lenkt unsere Aufmerksamkeit auf die soziale Moral. Leonardo verstand die Macht des Rufs, der, einmal befleckt, unglaublich schwer zu reparieren ist. In dieser Aussage warnt er uns, wachsam gegenüber unseren moralischen Handlungen und der Wahrnehmung anderer von uns zu sein. Der Ruf ist für Leonardo beständiger als das Leben selbst und prägt, wie wir lange nach unserem Tod in Erinnerung bleiben.

Leonardos Überlegungen zum Schlaf – „Was ist es, das die Menschen sehr begehren, es aber nicht kennen, während sie es besitzen? Es ist der Schlaf“ – zeigen seine Fähigkeit, philosophische Einsichten im Alltagsleben zu finden. Schlaf, eine universelle menschliche Erfahrung, wird selten geschätzt, während wir ihn haben, und doch wird er heiß begehrt, wenn er fehlt. Dies dient als Metapher für viele Aspekte des menschlichen Lebens: Wir erkennen oft den Wert von Dingen nicht, bis wir sie verloren haben. Leonardos Fähigkeit, aus einfachen Beobachtungen tiefgründige Bedeutungen abzuleiten, macht seine Reflexionen so zeitlos.

Sein Wort über Wein und Wasser – „Wein ist gut, aber Wasser ist am Tisch vorzuziehen“ – ist einfach, aber tiefgründig. Während er die Freuden des Lebens schätzen konnte, verstand er auch den Wert von Mäßigung und Einfachheit – eine Lektion, die mit dem heutigen Fokus auf ein achtsames Leben übereinstimmt.

Seine Bemerkung, dass „das Wissen über vergangene Zeiten und die Orte der Erde sowohl ein Schmuckstück als auch eine Nahrung für den menschlichen Geist ist“, spricht für die Bedeutung von Geschichte und Geografie bei der Formung des menschlichen Verständnisses. Für Leonardo war die Vergangenheit nicht nur etwas, das man um seiner selbst willen studierte, sondern eine Quelle der Weisheit, die den Geist nährt. Er glaubte an die Macht des Wissens, den menschlichen Zustand zu erhöhen, und seine Ehrfurcht vor der Geschichte unterstreicht die Bedeutung des Lernens von denen, die vor uns kamen.

Schließlich folgt Leonardos Reflexion über die Gerechtigkeit – „Gerechtigkeit erfordert Macht, Einsicht und Willen; und sie gleicht der Königin der Bienen“ – eine differenzierte Sicht auf diese zentrale menschliche Tugend. Für Leonardo ist Gerechtigkeit kein passives Konzept, sondern etwas, das Kraft, Weisheit und Entschlossenheit erfordert, um durchgesetzt zu werden. Sein Vergleich mit der Bienenkönigin deutet darauf hin, dass Gerechtigkeit für die Ordnung der Gesellschaft von zentraler Bedeutung ist, ebenso wie die Bienenkönigin für das Überleben des Bienenstocks. Diese Reflexion erinnert uns daran, dass Gerechtigkeit, wie die Biene, zart, aber kraftvoll ist und ständige Wachsamkeit erfordert, um aufrechterhalten zu werden.

Leonardos Reflexionen über die menschliche Natur sind sowohl praktisch als auch philosophisch und bieten Einsichten in die moralischen und ethischen Dimensionen des Lebens. Sein Fokus auf Erfahrung, Sprache, Ruf und Gerechtigkeit bietet einen Leitfaden für ein Leben in Integrität und Bewusstsein. Diese Beobachtungen, die in der humanistischen Tradition der Renaissance verwurzelt sind, haben auch heute noch Bestand und fordern uns auf, mit Achtsamkeit, Moral und Weisheit in die Welt um uns herum einzutreten.

Verschiedenes

-

Meide die Grundsätze jener Spekulanten, deren Argumente nicht durch Erfahrung bestätigt werden. b 4 v.

-

Meide jene Studien, bei denen die Arbeit mit dem Arbeiter stirbt. Forster in. 55 r.

-

Siehe, einige, die sich nichts anderes nennen können als ein Durchgang für Nahrung. Forster in. 74 v.

-